4.2 Distributed Computing

A distributed system is a network of autonomous computers that communicate with each other in order to achieve a goal. The computers in a distributed system are independent and do not physically share memory or processors. They communicate with each other using messages, pieces of information transferred from one computer to another over a network. Messages can communicate many things: computers can tell other computers to execute a procedures with particular arguments, they can send and receive packets of data, or send signals that tell other computers to behave a certain way.

Computers in a distributed system can have different roles. A computer's role depends on the goal of the system and the computer's own hardware and software properties. There are two predominant ways of organizing computers in a distributed system. The first is the client-server architecture, and the second is the peer-to-peer architecture.

4.2.1 Client/Server Systems

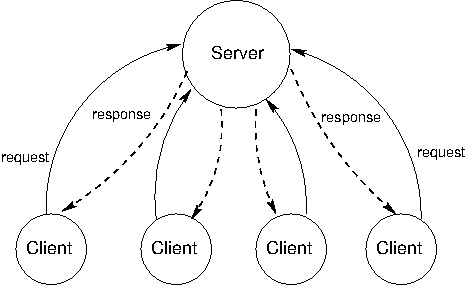

The client-server architecture is a way to dispense a service from a central source. There is a single server that provides a service, and multiple clients that communicate with the server to consume its products. In this architecture, clients and servers have different jobs. The server's job is to respond to service requests from clients, while a client's job is to use the data provided in response in order to perform some task.

The client-server model of communication can be traced back to the introduction of UNIX in the 1970's, but perhaps the most influential use of the model is the modern World Wide Web. An example of a client-server interaction is reading the New York Times online. When the web server at www.nytimes.com is contacted by a web browsing client (like Firefox), its job is to send back the HTML of the New York Times main page. This could involve calculating personalized content based on user account information sent by the client, and fetching appropriate advertisements. The job of the web browsing client is to render the HTML code sent by the server. This means displaying the images, arranging the content visually, showing different colors, fonts, and shapes and allowing users to interact with the rendered web page.

The concepts of client and server are powerful functional abstractions. A server is simply a unit that provides a service, possibly to multiple clients simultaneously, and a client is a unit that consumes the service. The clients do not need to know the details of how the service is provided, or how the data they are receiving is stored or calculated, and the server does not need to know how the data is going to be used.

On the web, we think of clients and servers as being on different machines, but even systems on a single machine can have client/server architectures. For example, signals from input devices on a computer need to be generally available to programs running on the computer. The programs are clients, consuming mouse and keyboard input data. The operating system's device drivers are the servers, taking in physical signals and serving them up as usable input.

A drawback of client-server systems is that the server is a single point of failure. It is the only component with the ability to dispense the service. There can be any number of clients, which are interchangeable and can come and go as necessary. If the server goes down, however, the system stops working. Thus, the functional abstraction created by the client-server architecture also makes it vulnerable to failure.

Another drawback of client-server systems is that resources become scarce if there are too many clients. Clients increase the demand on the system without contributing any computing resources. Client-server systems cannot shrink and grow with changing demand.

4.2.2 Peer-to-peer Systems

The client-server model is appropriate for service-oriented situations. However, there are other computational goals for which a more equal division of labor is a better choice. The term peer-to-peer is used to describe distributed systems in which labor is divided among all the components of the system. All the computers send and receive data, and they all contribute some processing power and memory. As a distributed system increases in size, its capacity of computational resources increases. In a peer-to-peer system, all components of the system contribute some processing power and memory to a distributed computation.

Division of labor among all participants is the identifying characteristic of a peer-to-peer system. This means that peers need to be able to communicate with each other reliably. In order to make sure that messages reach their intended destinations, peer-to-peer systems need to have an organized network structure. The components in these systems cooperate to maintain enough information about the locations of other components to send messages to intended destinations.

In some peer-to-peer systems, the job of maintaining the health of the network is taken on by a set of specialized components. Such systems are not pure peer-to-peer systems, because they have different types of components that serve different functions. The components that support a peer-to-peer network act like scaffolding: they help the network stay connected, they maintain information about the locations of different computers, and they help newcomers take their place within their neighborhood.

The most common applications of peer-to-peer systems are data transfer and data storage. For data transfer, each computer in the system contributes to send data over the network. If the destination computer is in a particular computer's neighborhood, that computer helps send data along. For data storage, the data set may be too large to fit on any single computer, or too valuable to store on just a single computer. Each computer stores a small portion of the data, and there may be multiple copies of the same data spread over different computers. When a computer fails, the data that was on it can be restored from other copies and put back when a replacement arrives.

Skype, the voice- and video-chat service, is an example of a data transfer application with a peer-to-peer architecture. When two people on different computers are having a Skype conversation, their communications are broken up into packets of 1s and 0s and transmitted through a peer-to-peer network. This network is composed of other people whose computers are signed into Skype. Each computer knows the location of a few other computers in its neighborhood. A computer helps send a packet to its destination by passing it on a neighbor, which passes it on to some other neighbor, and so on, until the packet reaches its intended destination. Skype is not a pure peer-to-peer system. A scaffolding network of supernodes is responsible for logging-in and logging-out users, maintaining information about the locations of their computers, and modifying the network structure to deal with users entering and leaving.

4.2.3 Modularity

The two architectures we have just considered -- peer-to-peer and client-server -- are designed to enforce modularity. Modularity is the idea that the components of a system should be black boxes with respect to each other. It should not matter how a component implements its behavior, as long as it upholds an interface: a specification for what outputs will result from inputs.

In chapter 2, we encountered interfaces in the context of dispatch functions and object-oriented programming. There, interfaces took the form of specifying the messages that objects should take, and how they should behave in response to them. For example, in order to uphold the "representable as strings" interface, an object must be able to respond to the __repr__ and __str__ messages, and output appropriate strings in response. How the generation of those strings is implemented is not part of the interface.

In distributed systems, we must consider program design that involves multiple computers, and so we extend this notion of an interface from objects and messages to full programs. An interface specifies the inputs that should be accepted and the outputs that should be returned in response to inputs. Interfaces are everywhere in the real world, and we often take them for granted. A familiar example is TV remotes. You can buy many different brands of remote for a modern TV, and they will all work. The only commonality between them is the "TV remote" interface. A piece of electronics obeys the "TV remote" interface as long as it sends the correct signals to your TV (the output) in response to when you press the power, volume, channel, or whatever other buttons (the input).

Modularity gives a system many advantages, and is a property of thoughtful system design. First, a modular system is easy to understand. This makes it easier to change and expand. Second, if something goes wrong with the system, only the defective components need to be replaced. Third, bugs or malfunctions are easy to localize. If the output of a component doesn't match the specifications of its interface, even though the inputs are correct, then that component is the source of the malfunction.

4.2.4 Message Passing

In distributed systems, components communicate with each other using message passing. A message has three essential parts: the sender, the recipient, and the content. The sender needs to be specified so that the recipient knows which component sent the message, and where to send replies. The recipient needs to be specified so that any computers who are helping send the message know where to direct it. The content of the message is the most variable. Depending on the function of the overall system, the content can be a piece of data, a signal, or instructions for the remote computer to evaluate a function with some arguments.

This notion of message passing is closely related to the message passing technique from Chapter 2, in which dispatch functions or dictionaries responded to string-valued messages. Within a program, the sender and receiver are identified by the rules of evaluation. In a distributed system however, the sender and receiver must be explicitly encoded in the message. Within a program, it is convenient to use strings to control the behavior of the dispatch function. In a distributed system, messages may need to be sent over a network, and may need to hold many different kinds of signals as 'data', so they are not always encoded as strings. In both cases, however, messages serve the same function. Different components (dispatch functions or computers) exchange them in order to achieve a goal that requires coordinating multiple modular components.

At a high level, message contents can be complex data structures, but at a low level, messages are simply streams of 1s and 0s sent over a network. In order to be usable, all messages sent over a network must be formatted according to a consistent message protocol.

A message protocol is a set of rules for encoding and decoding messages. Many message protocols specify that a message conform to a particular format, in which certain bits have a consistent meaning. A fixed format implies fixed encoding and decoding rules to generate and read that format. All the components in the distributed system must understand the protocol in order to communicate with each other. That way, they know which part of the message corresponds to which information.

Message protocols are not particular programs or software libraries. Instead, they are rules that can be applied by a variety of programs, even written in different programming languages. As a result, computers with vastly different software systems can participate in the same distributed system, simply by conforming to the message protocols that govern the system.

4.2.5 Messages on the World Wide Web

HTTP (short for Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is the message protocol that supports the world wide web. It specifies the format of messages exchanged between a web browser and a web server. All web browsers use the HTTP format to request pages from a web server, and all web servers use the HTTP format to send back their responses.

When you type in a URL into your web browser, say http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/UC_Berkeley , you are in fact telling your browser that it must request the page "wiki/UC_Berkeley" from the server called "en.wikipedia.org" using the "http" protocol. The sender of the message is your computer, the recipient is en.wikipedia.org, and the format of the message content is:

GET /wiki/UC_Berkeley HTTP/1.1

The first word is the type of the request, the next word is the resource that is requested, and after that is the name of the protocol (HTTP) and the version (1.1). (There are another types of requests, such as PUT, POST, and HEAD, that web browsers can also use).

The server sends back a reply. This time, the sender is en.wikipedia.org, the recipient is your computer, and the format of the message content is a header, followed by data:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Mon, 23 May 2011 22:38:34 GMT

Server: Apache/1.3.3.7 (Unix) (Red-Hat/Linux)

Last-Modified: Wed, 08 Jan 2011 23:11:55 GMT

Content-Type: text/html; charset=UTF-8

... web page content ...

On the first line, the words "200 OK" mean that there were no errors. The subsequent lines of the header give information about the server, the date, and the type of content being sent back. The header is separated from the actual content of the web page by a blank line.

If you have typed in a wrong web address, or clicked on a broken link, you may have seen a message like this error:

404 Error File Not Found

It means that the server sent back an HTTP header that started like this:

HTTP/1.1 404 Not Found

A fixed set of response codes is a common feature of a message protocol. Designers of protocols attempt to anticipate common messages that will be sent via the protocol and assign fixed codes to reduce transmission size and establish a common message semantics. In the HTTP protocol, the 200 response code indicates success, while 404 indicates an error that a resource was not found. A variety of other response codes exist in the HTTP 1.1 standard as well.

HTTP is a fixed format for communication, but it allows arbitrary web pages to be transmitted. Other protocols like this on the internet are XMPP, a popular protocol for instant messages, and FTP, a protocol for downloading and uploading files between client and server.