2.7 Generic Operations

In this chapter, we introduced compound data values, along with the technique of data abstraction using constructors and selectors. Using message passing, we endowed our abstract data types with behavior directly. Using the object metaphor, we bundled together the representation of data and the methods used to manipulate that data to modularize data-driven programs with local state.

However, we have yet to show that our object system allows us to combine together different types of objects flexibly in a large program. Message passing via dot expressions is only one way of building combined expressions with multiple objects. In this section, we explore alternate methods for combining and manipulating objects of different types.

2.7.1 String Conversion

We stated in the beginning of this chapter that an object value should behave like the kind of data it is meant to represent, including producing a string representation of itself. String representations of data values are especially important in an interactive language like Python, where the read-eval-print loop requires every value to have some sort of string representation.

String values provide a fundamental medium for communicating information among humans. Sequences of characters can be rendered on a screen, printed to paper, read aloud, converted to braille, or broadcast as Morse code. Strings are also fundamental to programming because they can represent Python expressions. For an object, we may want to generate a string that, when interpreted as a Python expression, evaluates to an equivalent object.

Python stipulates that all objects should produce two different string representations: one that is human-interpretable text and one that is a Python-interpretable expression. The constructor function for strings, str, returns a human-readable string. Where possible, the repr function returns a Python expression that evaluates to an equal object. The docstring for repr explains this property:

repr(object) -> string

Return the canonical string representation of the object.

For most object types, eval(repr(object)) == object.

The result of calling repr on the value of an expression is what Python prints in an interactive session.

>>> 12e12

12000000000000.0

>>> print(repr(12e12))

12000000000000.0

In cases where no representation exists that evaluates to the original value, Python produces a proxy.

>>> repr(min)

'<built-in function min>'

The str constructor often coincides with repr, but provides a more interpretable text representation in some cases. For instance, we see a difference between str and repr with dates.

>>> from datetime import date

>>> today = date(2011, 9, 12)

>>> repr(today)

'datetime.date(2011, 9, 12)'

>>> str(today)

'2011-09-12'

Defining the repr function presents a new challenge: we would like it to apply correctly to all data types, even those that did not exist when repr was implemented. We would like it to be a polymorphic function, one that can be applied to many (poly) different forms (morph) of data.

Message passing provides an elegant solution in this case: the repr function invokes a method called __repr__ on its argument.

>>> today.__repr__()

'datetime.date(2011, 9, 12)'

By implementing this same method in user-defined classes, we can extend the applicability of repr to any class we create in the future. This example highlights another benefit of message passing in general, that it provides a mechanism for extending the domain of existing functions to new object types.

The str constructor is implemented in a similar manner: it invokes a method called __str__ on its argument.

>>> today.__str__()

'2011-09-12'

These polymorphic functions are examples of a more general principle: certain functions should apply to multiple data types. The message passing approach exemplified here is only one of a family of techniques for implementing polymorphic functions. The remainder of this section explores some alternatives.

2.7.2 Multiple Representations

Data abstraction, using objects or functions, is a powerful tool for managing complexity. Abstract data types allow us to construct an abstraction barrier between the underlying representation of data and the functions or messages used to manipulate it. However, in large programs, it may not always make sense to speak of "the underlying representation" for a data type in a program. For one thing, there might be more than one useful representation for a data object, and we might like to design systems that can deal with multiple representations.

To take a simple example, complex numbers may be represented in two almost equivalent ways: in rectangular form (real and imaginary parts) and in polar form (magnitude and angle). Sometimes the rectangular form is more appropriate and sometimes the polar form is more appropriate. Indeed, it is perfectly plausible to imagine a system in which complex numbers are represented in both ways, and in which the functions for manipulating complex numbers work with either representation.

More importantly, large software systems are often designed by many people working over extended periods of time, subject to requirements that change over time. In such an environment, it is simply not possible for everyone to agree in advance on choices of data representation. In addition to the data-abstraction barriers that isolate representation from use, we need abstraction barriers that isolate different design choices from each other and permit different choices to coexist in a single program. Furthermore, since large programs are often created by combining pre-existing modules that were designed in isolation, we need conventions that permit programmers to incorporate modules into larger systems additively, that is, without having to redesign or re-implement these modules.

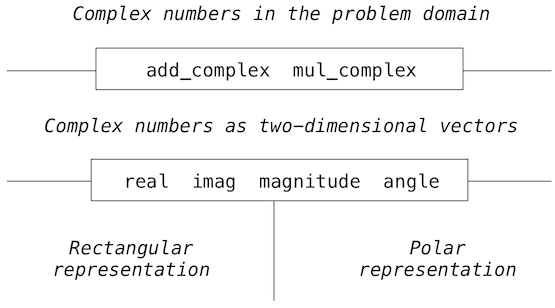

We begin with the simple complex-number example. We will see how message passing enables us to design separate rectangular and polar representations for complex numbers while maintaining the notion of an abstract "complex-number" object. We will accomplish this by defining arithmetic functions for complex numbers (add_complex, mul_complex) in terms of generic selectors that access parts of a complex number independent of how the number is represented. The resulting complex-number system contains two different kinds of abstraction barriers. They isolate higher-level operations from lower-level representations. In addition, there is a vertical barrier that gives us the ability to separately design alternative representations.

As a side note, we are developing a system that performs arithmetic operations on complex numbers as a simple but unrealistic example of a program that uses generic operations. A complex number type is actually built into Python, but for this example we will implement our own.

Like rational numbers, complex numbers are naturally represented as pairs. The set of complex numbers can be thought of as a two-dimensional space with two orthogonal axes, the real axis and the imaginary axis. From this point of view, the complex number z = x + y * i (where i*i = -1) can be thought of as the point in the plane whose real coordinate is x and whose imaginary coordinate is y. Adding complex numbers involves adding their respective x and y coordinates.

When multiplying complex numbers, it is more natural to think in terms of representing a complex number in polar form, as a magnitude and an angle. The product of two complex numbers is the vector obtained by stretching one complex number by a factor of the length of the other, and then rotating it through the angle of the other.

Thus, there are two different representations for complex numbers, which are appropriate for different operations. Yet, from the viewpoint of someone writing a program that uses complex numbers, the principle of data abstraction suggests that all the operations for manipulating complex numbers should be available regardless of which representation is used by the computer.

Interfaces. Message passing not only provides a method for coupling behavior and data, it allows different data types to respond to the same message in different ways. A shared message that elicits similar behavior from different object classes is a powerful method of abstraction.

As we have seen, an abstract data type is defined by constructors, selectors, and additional behavior conditions. A closely related concept is an interface, which is a set of shared messages, along with a specification of what they mean. Objects that respond to the special __repr__ and __str__ methods all implement a common interface of types that can be represented as strings.

In the case of complex numbers, the interface needed to implement arithmetic consists of four messages: real, imag, magnitude, and angle. We can implement addition and multiplication in terms of these messages.

We can have two different abstract data types for complex numbers that differ in their constructors.

ComplexRIconstructs a complex number from real and imaginary parts.ComplexMAconstructs a complex number from a magnitude and angle.

With these messages and constructors, we can implement complex arithmetic.

>>> def add_complex(z1, z2):

return ComplexRI(z1.real + z2.real, z1.imag + z2.imag)

>>> def mul_complex(z1, z2):

return ComplexMA(z1.magnitude * z2.magnitude, z1.angle + z2.angle)

The relationship between the terms "abstract data type" (ADT) and "interface" is subtle. An ADT includes ways of building complex data types, manipulating them as units, and selecting for their components. In an object-oriented system, an ADT corresponds to a class, although we have seen that an object system is not needed to implement an ADT. An interface is a set of messages that have associated meanings, and which may or may not include selectors. Conceptually, an ADT describes a full representational abstraction of some kind of thing, whereas an interface specifies a set of behaviors that may be shared across many things.

Properties. We would like to use both types of complex numbers interchangeably, but it would be wasteful to store redundant information about each number. We would like to store either the real-imaginary representation or the magnitude-angle representation.

Python has a simple feature for computing attributes on the fly from zero-argument functions. The @property decorator allows functions to be called without the standard call expression syntax. An implementation of complex numbers in terms of real and imaginary parts illustrates this point.

>>> from math import atan2

>>> class ComplexRI(object):

def __init__(self, real, imag):

self.real = real

self.imag = imag

@property

def magnitude(self):

return (self.real ** 2 + self.imag ** 2) ** 0.5

@property

def angle(self):

return atan2(self.imag, self.real)

def __repr__(self):

return 'ComplexRI({0}, {1})'.format(self.real, self.imag)

A second implementation using magnitude and angle provides the same interface because it responds to the same set of messages.

>>> from math import sin, cos

>>> class ComplexMA(object):

def __init__(self, magnitude, angle):

self.magnitude = magnitude

self.angle = angle

@property

def real(self):

return self.magnitude * cos(self.angle)

@property

def imag(self):

return self.magnitude * sin(self.angle)

def __repr__(self):

return 'ComplexMA({0}, {1})'.format(self.magnitude, self.angle)

In fact, our implementations of add_complex and mul_complex are now complete; either class of complex number can be used for either argument in either complex arithmetic function. It is worth noting that the object system does not explicitly connect the two complex types in any way (e.g., through inheritance). We have implemented the complex number abstraction by sharing a common set of messages, an interface, across the two classes.

>>> from math import pi

>>> add_complex(ComplexRI(1, 2), ComplexMA(2, pi/2))

ComplexRI(1.0000000000000002, 4.0)

>>> mul_complex(ComplexRI(0, 1), ComplexRI(0, 1))

ComplexMA(1.0, 3.141592653589793)

The interface approach to encoding multiple representations has appealing properties. The class for each representation can be developed separately; they must only agree on the names of the attributes they share. The interface is also additive. If another programmer wanted to add a third representation of complex numbers to the same program, they would only have to create another class with the same attributes.

Special methods. The built-in mathematical operators can be extended in much the same way as repr; there are special method names corresponding to Python operators for arithmetic, logical, and sequence operations.

To make our code more legible, we would perhaps like to use the + and * operators directly when adding and multiplying complex numbers. Adding the following methods to both of our complex number classes will enable these operators to be used, as well as the add and mul functions in the operator module:

>>> ComplexRI.__add__ = lambda self, other: add_complex(self, other)

>>> ComplexMA.__add__ = lambda self, other: add_complex(self, other)

>>> ComplexRI.__mul__ = lambda self, other: mul_complex(self, other)

>>> ComplexMA.__mul__ = lambda self, other: mul_complex(self, other)

Now, we can use infix notation with our user-defined classes.

>>> ComplexRI(1, 2) + ComplexMA(2, 0)

ComplexRI(3.0, 2.0)

>>> ComplexRI(0, 1) * ComplexRI(0, 1)

ComplexMA(1.0, 3.141592653589793)

Further reading. To evaluate expressions that contain the + operator, Python checks for special methods on both the left and right operands of the expression. First, Python checks for an __add__ method on the value of the left operand, then checks for an __radd__ method on the value of the right operand. If either is found, that method is invoked with the value of the other operand as its argument.

Similar protocols exist for evaluating expressions that contain any kind of operator in Python, including slice notation and Boolean operators. The Python docs list the exhaustive set of method names for operators. Dive into Python 3 has a chapter on special method names that describes many details of their use in the Python interpreter.

2.7.3 Generic Functions

Our implementation of complex numbers has made two data types interchangeable as arguments to the add_complex and mul_complex functions. Now we will see how to use this same idea not only to define operations that are generic over different representations but also to define operations that are generic over different kinds of arguments that do not share a common interface.

The operations we have defined so far treat the different data types as being completely independent. Thus, there are separate packages for adding, say, two rational numbers, or two complex numbers. What we have not yet considered is the fact that it is meaningful to define operations that cross the type boundaries, such as the addition of a complex number to a rational number. We have gone to great pains to introduce barriers between parts of our programs so that they can be developed and understood separately.

We would like to introduce the cross-type operations in some carefully controlled way, so that we can support them without seriously violating our abstraction boundaries. There is a tension between the outcomes we desire: we would like to be able to add a complex number to a rational number, and we would like to do so using a generic add function that does the right thing with all numeric types. At the same time, we would like to separate the concerns of complex numbers and rational numbers whenever possible, in order to maintain a modular program.

Let us revise our implementation of rational numbers to use Python's built-in object system. As before, we will store a rational number as a numerator and denominator in lowest terms.

>>> from fractions import gcd

>>> class Rational(object):

def __init__(self, numer, denom):

g = gcd(numer, denom)

self.numer = numer // g

self.denom = denom // g

def __repr__(self):

return 'Rational({0}, {1})'.format(self.numer, self.denom)

Adding and multiplying rational numbers in this new implementation is similar to before.

>>> def add_rational(x, y):

nx, dx = x.numer, x.denom

ny, dy = y.numer, y.denom

return Rational(nx * dy + ny * dx, dx * dy)

>>> def mul_rational(x, y):

return Rational(x.numer * y.numer, x.denom * y.denom)

Type dispatching. One way to handle cross-type operations is to design a different function for each possible combination of types for which the operation is valid. For example, we could extend our complex number implementation so that it provides a function for adding complex numbers to rational numbers. We can provide this functionality generically using a technique called dispatching on type.

The idea of type dispatching is to write functions that first inspect the type of argument they have received, and then execute code that is appropriate for the type. In Python, the type of an object can be inspected with the built-in type function.

>>> def iscomplex(z):

return type(z) in (ComplexRI, ComplexMA)

>>> def isrational(z):

return type(z) == Rational

In this case, we are relying on the fact that each object knows its type, and we can look up that type using the Python type function. Even if the type function were not available, we could imagine implementing iscomplex and isrational in terms of a shared class attribute for Rational, ComplexRI, and ComplexMA.

Now consider the following implementation of add, which explicitly checks the type of both arguments. We will not use Python's special methods (i.e., __add__) in this example.

>>> def add_complex_and_rational(z, r):

return ComplexRI(z.real + r.numer/r.denom, z.imag)

>>> def add(z1, z2):

"""Add z1 and z2, which may be complex or rational."""

if iscomplex(z1) and iscomplex(z2):

return add_complex(z1, z2)

elif iscomplex(z1) and isrational(z2):

return add_complex_and_rational(z1, z2)

elif isrational(z1) and iscomplex(z2):

return add_complex_and_rational(z2, z1)

else:

return add_rational(z1, z2)

This simplistic approach to type dispatching, which uses a large conditional statement, is not additive. If another numeric type were included in the program, we would have to re-implement add with new clauses.

We can create a more flexible implementation of add by implementing type dispatch through a dictionary. The first step in extending the flexibility of add will be to create a tag set for our classes that abstracts away from the two implementations of complex numbers.

>>> def type_tag(x):

return type_tag.tags[type(x)]

>>> type_tag.tags = {ComplexRI: 'com', ComplexMA: 'com', Rational: 'rat'}

Next, we use these type tags to index a dictionary that stores the different ways of adding numbers. The keys of the dictionary are tuples of type tags, and the values are type-specific addition functions.

>>> def add(z1, z2):

types = (type_tag(z1), type_tag(z2))

return add.implementations[types](z1, z2)

This definition of add does not have any functionality itself; it relies entirely on a dictionary called add.implementations to implement addition. We can populate that dictionary as follows.

>>> add.implementations = {}

>>> add.implementations[('com', 'com')] = add_complex

>>> add.implementations[('com', 'rat')] = add_complex_and_rational

>>> add.implementations[('rat', 'com')] = lambda x, y: add_complex_and_rational(y, x)

>>> add.implementations[('rat', 'rat')] = add_rational

This dictionary-based approach to dispatching is additive, because add.implementations and type_tag.tags can always be extended. Any new numeric type can "install" itself into the existing system by adding new entries to these dictionaries.

While we have introduced some complexity to the system, we now have a generic, extensible add function that handles mixed types.

>>> add(ComplexRI(1.5, 0), Rational(3, 2))

ComplexRI(3.0, 0)

>>> add(Rational(5, 3), Rational(1, 2))

Rational(13, 6)

Data-directed programming. Our dictionary-based implementation of add is not addition-specific at all; it does not contain any direct addition logic. It only implements addition because we happen to have populated its implementations dictionary with functions that perform addition.

A more general version of generic arithmetic would apply arbitrary operators to arbitrary types and use a dictionary to store implementations of various combinations. This fully generic approach to implementing methods is called data-directed programming. In our case, we can implement both generic addition and multiplication without redundant logic.

>>> def apply(operator_name, x, y):

tags = (type_tag(x), type_tag(y))

key = (operator_name, tags)

return apply.implementations[key](x, y)

In this generic apply function, a key is constructed from the operator name (e.g., 'add') and a tuple of type tags for the arguments. Implementations are also populated using these tags. We enable support for multiplication on complex and rational numbers below.

>>> def mul_complex_and_rational(z, r):

return ComplexMA(z.magnitude * r.numer / r.denom, z.angle)

>>> mul_rational_and_complex = lambda r, z: mul_complex_and_rational(z, r)

>>> apply.implementations = {('mul', ('com', 'com')): mul_complex,

('mul', ('com', 'rat')): mul_complex_and_rational,

('mul', ('rat', 'com')): mul_rational_and_complex,

('mul', ('rat', 'rat')): mul_rational}

We can also include the addition implementations from add to apply, using the dictionary update method.

>>> adders = add.implementations.items()

>>> apply.implementations.update({('add', tags):fn for (tags, fn) in adders})

Now that apply supports 8 different implementations in a single table, we can use it to manipulate rational and complex numbers quite generically.

>>> apply('add', ComplexRI(1.5, 0), Rational(3, 2))

ComplexRI(3.0, 0)

>>> apply('mul', Rational(1, 2), ComplexMA(10, 1))

ComplexMA(5.0, 1)

This data-directed approach does manage the complexity of cross-type operators, but it is cumbersome. With such a system, the cost of introducing a new type is not just writing methods for that type, but also the construction and installation of the functions that implement the cross-type operations. This burden can easily require much more code than is needed to define the operations on the type itself.

While the techniques of dispatching on type and data-directed programming do create additive implementations of generic functions, they do not effectively separate implementation concerns; implementors of the individual numeric types need to take account of other types when writing cross-type operations. Combining rational numbers and complex numbers isn't strictly the domain of either type. Formulating coherent policies on the division of responsibility among types can be an overwhelming task in designing systems with many types and cross-type operations.

Coercion. In the general situation of completely unrelated operations acting on completely unrelated types, implementing explicit cross-type operations, cumbersome though it may be, is the best that one can hope for. Fortunately, we can sometimes do better by taking advantage of additional structure that may be latent in our type system. Often the different data types are not completely independent, and there may be ways by which objects of one type may be viewed as being of another type. This process is called coercion. For example, if we are asked to arithmetically combine a rational number with a complex number, we can view the rational number as a complex number whose imaginary part is zero. By doing so, we transform the problem to that of combining two complex numbers, which can be handled in the ordinary way by add_complex and mul_complex.

In general, we can implement this idea by designing coercion functions that transform an object of one type into an equivalent object of another type. Here is a typical coercion function, which transforms a rational number to a complex number with zero imaginary part:

>>> def rational_to_complex(x):

return ComplexRI(x.numer/x.denom, 0)

Now, we can define a dictionary of coercion functions. This dictionary could be extended as more numeric types are introduced.

>>> coercions = {('rat', 'com'): rational_to_complex}

It is not generally possible to coerce an arbitrary data object of each type into all other types. For example, there is no way to coerce an arbitrary complex number to a rational number, so there will be no such conversion implementation in the coercions dictionary.

Using the coercions dictionary, we can write a function called coerce_apply, which attempts to coerce arguments into values of the same type, and only then applies an operator. The implementations dictionary of coerce_apply does not include any cross-type operator implementations.

>>> def coerce_apply(operator_name, x, y):

tx, ty = type_tag(x), type_tag(y)

if tx != ty:

if (tx, ty) in coercions:

tx, x = ty, coercions[(tx, ty)](x)

elif (ty, tx) in coercions:

ty, y = tx, coercions[(ty, tx)](y)

else:

return 'No coercion possible.'

key = (operator_name, tx)

return coerce_apply.implementations[key](x, y)

The implementations of coerce_apply require only one type tag, because they assume that both values share the same type tag. Hence, we require only four implementations to support generic arithmetic over complex and rational numbers.

>>> coerce_apply.implementations = {('mul', 'com'): mul_complex,

('mul', 'rat'): mul_rational,

('add', 'com'): add_complex,

('add', 'rat'): add_rational}

With these implementations in place, coerce_apply can replace apply.

>>> coerce_apply('add', ComplexRI(1.5, 0), Rational(3, 2))

ComplexRI(3.0, 0)

>>> coerce_apply('mul', Rational(1, 2), ComplexMA(10, 1))

ComplexMA(5.0, 1.0)

This coercion scheme has some advantages over the method of defining explicit cross-type operations. Although we still need to write coercion functions to relate the types, we need to write only one function for each pair of types rather than a different functions for each collection of types and each generic operation. What we are counting on here is the fact that the appropriate transformation between types depends only on the types themselves, not on the particular operation to be applied.

Further advantages come from extending coercion. Some more sophisticated coercion schemes do not just try to coerce one type into another, but instead may try to coerce two different types each into a third common type. Consider a rhombus and a rectangle: neither is a special case of the other, but both can be viewed as quadrilaterals. Another extension to coercion is iterative coercion, in which one data type is coerced into another via intermediate types. Consider that an integer can be converted into a real number by first converting it into a rational number, then converting that rational number into a real number. Chaining coercion in this way can reduce the total number of coercion functions that are required by a program.

Despite its advantages, coercion does have potential drawbacks. For one, coercion functions can lose information when they are applied. In our example, rational numbers are exact representations, but become approximations when they are converted to complex numbers.

Some programming languages have automatic coercion systems built in. In fact, early versions of Python had a __coerce__ special method on objects. In the end, the complexity of the built-in coercion system did not justify its use, and so it was removed. Instead, particular operators apply coercion to their arguments as needed. Operators are implemented as method calls on user defined types using special methods like __add__ and __mul__. It is left up to you, the user, to decide whether to employ type dispatching, data-directed programming, message passing, or coercion in order to implement generic functions in your programs.