2.2 Data Abstraction

As we consider the wide set of things in the world that we would like to represent in our programs, we find that most of them have compound structure. A date has a year, a month, and a day; a geographic position has a latitude and a longitude. To represent positions, we would like our programming language to have the capacity to "glue together" a latitude and longitude to form a pair --- a compound data value --- that our programs could manipulate in a way that would be consistent with the fact that we regard a position as a single conceptual unit, which has two parts.

The use of compound data also enables us to increase the modularity of our programs. If we can manipulate geographic positions directly as objects in their own right, then we can separate the part of our program that deals with values per se from the details of how those values may be represented. The general technique of isolating the parts of a program that deal with how data are represented from the parts of a program that deal with how those data are manipulated is a powerful design methodology called data abstraction. Data abstraction makes programs much easier to design, maintain, and modify.

Data abstraction is similar in character to functional abstraction. When we create a functional abstraction, the details of how a function is implemented can be suppressed, and the particular function itself can be replaced by any other function with the same overall behavior. In other words, we can make an abstraction that separates the way the function is used from the details of how the function is implemented. Analogously, data abstraction is a methodology that enables us to isolate how a compound data object is used from the details of how it is constructed.

The basic idea of data abstraction is to structure programs so that they operate on abstract data. That is, our programs should use data in such a way as to make as few assumptions about the data as possible. At the same time, a concrete data representation is defined, independently of the programs that use the data. The interface between these two parts of our system will be a set of functions, called selectors and constructors, that implement the abstract data in terms of the concrete representation. To illustrate this technique, we will consider how to design a set of functions for manipulating rational numbers.

As you read the next few sections, keep in mind that most Python code written today uses very high-level abstract data types that are built into the language, like classes, dictionaries, and lists. Since we're building up an understanding of how these abstractions work, we can't use them yet ourselves. As a consequence, we will write some code that isn't Pythonic --- it's not necessarily the typical way to implement our ideas in the language. What we write is instructive, however, because it demonstrates how these abstractions can be constructed! Remember that computer science isn't just about learning to use programming languages, but also learning how they work.

2.2.1 Example: Arithmetic on Rational Numbers

Recall that a rational number is a ratio of integers, and rational numbers constitute an important sub-class of real numbers. A rational number like 1/3 or 17/29 is typically written as:

<numerator>/<denominator>

where both the <numerator> and <denominator> are placeholders for integer values. Both parts are needed to exactly characterize the value of the rational number.

Rational numbers are important in computer science because they, like integers, can be represented exactly. Irrational numbers (like pi or e or sqrt(2)) are instead approximated using a finite binary expansion. Thus, working with rational numbers should, in principle, allow us to avoid approximation errors in our arithmetic.

However, as soon as we actually divide the numerator by the denominator, we can be left with a truncated decimal approximation (a float).

>>> 1/3

0.3333333333333333

and the problems with this approximation appear when we start to conduct tests:

>>> 1/3 == 0.333333333333333300000 # Beware of approximations

True

How computers approximate real numbers with finite-length decimal expansions is a topic for another class. The important idea here is that by representing rational numbers as ratios of integers, we avoid the approximation problem entirely. Hence, we would like to keep the numerator and denominator separate for the sake of precision, but treat them as a single unit.

We know from using functional abstractions that we can start programming productively before we have an implementation of some parts of our program. Let us begin by assuming that we already have a way of constructing a rational number from a numerator and a denominator. We also assume that, given a rational number, we have a way of extracting (or selecting) its numerator and its denominator. Let us further assume that the constructor and selectors are available as the following three functions:

make_rat(n, d)returns the rational number with numeratornand denominatord.numer(x)returns the numerator of the rational numberx.denom(x)returns the denominator of the rational numberx.

We are using here a powerful strategy of synthesis: wishful thinking. We haven't yet said how a rational number is represented, or how the functions numer, denom, and make_rat should be implemented. Even so, if we did have these three functions, we could then add, multiply, and test equality of rational numbers by calling them:

>>> def add_rat(x, y):

nx, dx = numer(x), denom(x)

ny, dy = numer(y), denom(y)

return make_rat(nx * dy + ny * dx, dx * dy)

>>> def mul_rat(x, y):

return make_rat(numer(x) * numer(y), denom(x) * denom(y))

>>> def eq_rat(x, y):

return numer(x) * denom(y) == numer(y) * denom(x)

Now we have the operations on rational numbers defined in terms of the selector functions numer and denom, and the constructor function make_rat, but we haven't yet defined these functions. What we need is some way to glue together a numerator and a denominator into a unit.

2.2.2 Tuples

To enable us to implement the concrete level of our data abstraction, Python provides a compound structure called a tuple, which can be constructed by separating values by commas. Although not strictly required, parentheses almost always surround tuples.

>>> (1, 2)

(1, 2)

The elements of a tuple can be unpacked in two ways. The first way is via our familiar method of multiple assignment.

>>> pair = (1, 2)

>>> pair

(1, 2)

>>> x, y = pair

>>> x

1

>>> y

2

In fact, multiple assignment has been creating and unpacking tuples all along.

A second method for accessing the elements in a tuple is by the indexing operator, written as square brackets.

>>> pair[0]

1

>>> pair[1]

2

Tuples in Python (and sequences in most other programming languages) are 0-indexed, meaning that the index 0 picks out the first element, index 1 picks out the second, and so on. One intuition that underlies this indexing convention is that the index represents how far an element is offset from the beginning of the tuple.

The equivalent function for the element selection operator is called getitem, and it also uses 0-indexed positions to select elements from a tuple.

>>> from operator import getitem

>>> getitem(pair, 0)

1

Tuples are native types, which means that there are built-in Python operators to manipulate them. We'll return to the full properties of tuples shortly. At present, we are only interested in how tuples can serve as the glue that implements abstract data types.

Representing Rational Numbers. Tuples offer a natural way to implement rational numbers as a pair of two integers: a numerator and a denominator. We can implement our constructor and selector functions for rational numbers by manipulating 2-element tuples.

>>> def make_rat(n, d):

return (n, d)

>>> def numer(x):

return getitem(x, 0)

>>> def denom(x):

return getitem(x, 1)

A function for printing rational numbers completes our implementation of this abstract data type.

>>> def str_rat(x):

"""Return a string 'n/d' for numerator n and denominator d."""

return '{0}/{1}'.format(numer(x), denom(x))

Together with the arithmetic operations we defined earlier, we can manipulate rational numbers with the functions we have defined.

>>> half = make_rat(1, 2)

>>> str_rat(half)

'1/2'

>>> third = make_rat(1, 3)

>>> str_rat(mul_rat(half, third))

'1/6'

>>> str_rat(add_rat(third, third))

'6/9'

As the final example shows, our rational-number implementation does not reduce rational numbers to lowest terms. We can remedy this by changing make_rat. If we have a function for computing the greatest common denominator of two integers, we can use it to reduce the numerator and the denominator to lowest terms before constructing the pair. As with many useful tools, such a function already exists in the Python Library.

>>> from fractions import gcd

>>> def make_rat(n, d):

g = gcd(n, d)

return (n//g, d//g)

The double slash operator, //, expresses integer division, which rounds down the fractional part of the result of division. Since we know that g divides both n and d evenly, integer division is exact in this case. Now we have

>>> str_rat(add_rat(third, third))

'2/3'

as desired. This modification was accomplished by changing the constructor without changing any of the functions that implement the actual arithmetic operations.

Further reading. The str_rat implementation above uses format strings, which contain placeholders for values. The details of how to use format strings and the format method appear in the formatting strings section of Dive Into Python 3.

2.2.3 Abstraction Barriers

Before continuing with more examples of compound data and data abstraction, let us consider some of the issues raised by the rational number example. We defined operations in terms of a constructor make_rat and selectors numer and denom. In general, the underlying idea of data abstraction is to identify for each type of value a basic set of operations in terms of which all manipulations of values of that type will be expressed, and then to use only those operations in manipulating the data.

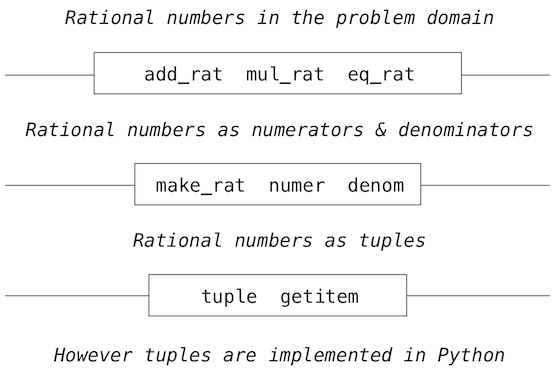

We can envision the structure of the rational number system as a series of layers.

The horizontal lines represent abstraction barriers that isolate different levels of the system. At each level, the barrier separates the functions (above) that use the data abstraction from the functions (below) that implement the data abstraction. Programs that use rational numbers manipulate them solely in terms of the their arithmetic functions: add_rat, mul_rat, and eq_rat. These, in turn, are implemented solely in terms of the constructor and selectors make_rat, numer, and denom, which themselves are implemented in terms of tuples. The details of how tuples are implemented are irrelevant to the rest of the layers as long as tuples enable the implementation of the selectors and constructor.

At each layer, the functions within the box enforce the abstraction boundary because they are the only functions that depend upon both the representation above them (by their use) and the implementation below them (by their definitions). In this way, abstraction barriers are expressed as sets of functions.

Abstraction barriers provide many advantages. One advantage is that they makes programs much easier to maintain and to modify. The fewer functions that depend on a particular representation, the fewer changes are required when one wants to change that representation.

2.2.4 The Properties of Data

We began the rational-number implementation by implementing arithmetic operations in terms of three unspecified functions: make_rat, numer, and denom. At that point, we could think of the operations as being defined in terms of data objects --- numerators, denominators, and rational numbers --- whose behavior was specified by the latter three functions.

But what exactly is meant by data? It is not enough to say "whatever is implemented by the given selectors and constructors." We need to guarantee that these functions together specify the right behavior. That is, if we construct a rational number x from integers n and d, then it should be the case that numer(x)/denom(x) is equal to n/d.

In general, we can think of an abstract data type as defined by some collection of selectors and constructors, together with some behavior conditions. As long as the behavior conditions are met (such as the division property above), these functions constitute a valid representation of the data type.

This point of view can be applied to other data types as well, such as the two-element tuple that we used in order to implement rational numbers. We never actually said much about what a tuple was, only that the language supplied operators to create and manipulate tuples. We can now describe the behavior conditions of two-element tuples, also called pairs, that are relevant to the problem of representing rational numbers.

In order to implement rational numbers, we needed a form of glue for two integers, which had the following behavior:

- If a pair

pwas constructed from valuesxandy, thengetitem_pair(p, 0)returnsx, andgetitem_pair(p, 1)returnsy.

We can implement functions make_pair and getitem_pair that fulfill this description just as well as a tuple.

>>> def make_pair(x, y):

"""Return a function that behaves like a pair."""

def dispatch(m):

if m == 0:

return x

elif m == 1:

return y

return dispatch

>>> def getitem_pair(p, i):

"""Return the element at index i of pair p."""

return p(i)

With this implementation, we can create and manipulate pairs.

>>> p = make_pair(1, 2)

>>> getitem_pair(p, 0)

1

>>> getitem_pair(p, 1)

2

This use of functions corresponds to nothing like our intuitive notion of what data should be. Nevertheless, these functions suffice to represent compound data in our programs.

The subtle point to notice is that the value returned by make_pair is a function called dispatch, which takes an argument m and returns either x or y. Then, getitem_pair calls this function to retrieve the appropriate value. We will return to the topic of dispatch functions several times throughout this chapter.

The point of exhibiting the functional representation of a pair is not that Python actually works this way (tuples are implemented more directly, for efficiency reasons) but that it could work this way. The functional representation, although obscure, is a perfectly adequate way to represent pairs, since it fulfills the only conditions that pairs need to fulfill. This example also demonstrates that the ability to manipulate functions as values automatically provides us the ability to represent compound data.