4.3 Parallel Computing

Computers get faster and faster every year. In 1965, Intel co-founder Gordon Moore made a prediction about how much faster computers would get with time. Based on only five data points, he extrapolated that the number of transistors that could inexpensively be fit onto a chip would double every two years. Almost 50 years later, his prediction, now called Moore's law, remains startlingly accurate.

Despite this explosion in speed, computers aren't able to keep up with the scale of data becoming available. By some estimates, advances in gene sequencing technology will make gene-sequence data available more quickly than processors are getting faster. In other words, for genetic data, computers are become less and less able to cope with the scale of processing problems each year, even though the computers themselves are getting faster.

To circumvent physical and mechanical constraints on individual processor speed, manufacturers are turning to another solution: multiple processors. If two, or three, or more processors are available, then many programs can be executed more quickly. While one processor is doing one aspect of some computation, others can work on another. All of them can share the same data, but the work will proceed in parallel.

In order to be able to work together, multiple processors need to be able to share information with each other. This is accomplished using a shared-memory environment. The variables, objects, and data structures in that environment are accessible to all the processes.The role of a processor in computation is to carry out the evaluation and execution rules of a programming language. In a shared memory model, different processes may execute different statements, but any statement can affect the shared environment.

4.3.1 The Problem with Shared State

Sharing state between multiple processes creates problems that a single-process environments do not have. To understand why, let us look the following simple calculation:

x = 5

x = square(x)

x = x + 1

The value of x is time-dependent. At first, it is 5, then, some time later, it is 25, and then finally, it is 26. In a single-process environment, this time-dependence is is not a problem. The value of x at the end is always 26. The same cannot be said, however, if multiple processes exist. Suppose we executed the last 2 lines of above code in parallel: one processor executes x = square(x) and the other executes x = x+1. Each of these assignment statements involves looking up the value currently bound to x, then updating that binding with a new value. Let us assume that since x is shared, only a single process will read or write it at a time. Even so, the order of the reads and writes may vary. For instance, the example below shows a series of steps for each of two processes, P1 and P2. Each step is a part of the evaluation process described briefly, and time proceeds from top to bottom:

P1 P2

read x: 5

read x: 5

calculate 5*5: 25 calculate 5+1: 6

write 25 -> x

write x-> 6

In this order, the final value of x is 6. If we do not coordinate the two processes, we could have another order with a different result:

P1 P2

read x: 5

read x: 5 calculate 5+1: 6

calculate 5*5: 25 write x->6

write 25 -> x

In this ordering, x would be 25. In fact, there are multiple possibilities depending on the order in which the processes execute their lines. The final value of x could end up being 5, 25, or the intended value, 26.

The preceding example is trivial. square(x) and x = x + 1 are simple calculations that are fast. We don't lose much time by forcing one to go after the other. But what about situations in which parallelization is essential? An example of such a situation is banking. At any given time, there may be thousands of people wanting to make transactions with their bank accounts: they may want to swipe their cards at shops, deposit checks, transfer money, or pay bills. Even a single account may have multiple transactions active at the same time.

Let us look at how the make_withdraw function from Chapter 2, modified below to print the balance after updating it rather than return it. We are interested in how this function will perform in a concurrent situation.

>>> def make_withdraw(balance):

def withdraw(amount):

nonlocal balance

if amount > balance:

print('Insufficient funds')

else:

balance = balance - amount

print(balance)

return withdraw

Now imagine that we create an account with $10 in it. Let us think about what happens if we withdraw too much money from the account. If we do these transactions in order, we receive an insufficient funds message.

>>> w = make_withdraw(10)

>>> w(8)

2

>>> w(7)

'Insufficient funds'

In parallel, however, there can be many different outcomes. One possibility appears below:

P1: w(8) P2: w(7)

read balance: 10

read amount: 8 read balance: 10

8 > 10: False read amount: 7

if False 7 > 10: False

10 - 8: 2 if False

write balance -> 2 10 - 7: 3

read balance: 2 write balance -> 3

print 2 read balance: 3

print 3

This particular example gives an incorrect outcome of 3. It is as if the w(8) transaction never happened! Other possible outcomes are 2, and 'Insufficient funds'. The source of the problems are the following: if P2 reads balance before P1 has written to balance (or vice versa), P2's state is inconsistent. The value of balance that P2 has read is obsolete, and P1 is going to change it. P2 doesn't know that and will overwrite it with an inconsistent value.

These example shows that parallelizing code is not as easy as dividing up the lines between multiple processors and having them be executed. The order in which variables are read and written matters.

A tempting way to enforce correctness is to stipulate that no two programs that modify shared data can run at the same time. For banking, unfortunately, this would mean that only one transaction could proceed at a time, since all transactions modify shared data. Intuitively, we understand that there should be no problem allowing 2 different people to perform transactions on completely separate accounts simultaneously. Somehow, those two operations do not interfere with each other the same way that simultaneous operations on the same account interfere with each other. Moreover, there is no harm in letting processes run concurrently when they are not reading or writing.

4.3.2 Correctness in Parallel Computation

There are two criteria for correctness in parallel computation environments. The first is that the outcome should always be the same. The second is that the outcome should be the same as if the code was executed in serial.

The first condition says that we must avoid the variability shown in the previous section, in which interleaving the reads and writes in different ways produces different results. In the example in which we withdrew w(8) and w(7) from a $10 account, this condition says that we must always return the same answer independent of the order in which P1's and P2's instructions are executed. Somehow, we must write our programs in such a way that, no matter how they are interleaved with each other, they should always produce the same result.

The second condition pins down which of the many possible outcomes is correct. In the example in which we evaluated w(7) and w(8) from a $10 account, this condition says that the result must always come out to be Insufficient funds, and not 2 or 3.

Problems arise in parallel computation when one process influences another during critical sections of a program. These are sections of code that need to be executed as if they were a single instruction, but are actually made up of smaller statements. A program's execution is conducted as a series of atomic hardware instructions, which are instructions that cannot be broken in to smaller units or interrupted because of the design of the processor. In order to behave correctly in concurrent situations, the critical sections in a programs code need to be have atomicity -- a guarantee that they will not be interrupted by any other code.

To enforce the atomicity of critical sections in a program's code under concurrency , there need to be ways to force processes to either serialize or synchronize with each other at important times. Serialization means that only one process runs at a time -- that they temporarily act as if they were being executed in serial. Synchronization takes two forms. The first is mutual exclusion, processes taking turns to access a variable, and the second is conditional synchronization, processes waiting until a condition is satisfied (such as other processes having finished their task) before continuing. This way, when one program is about to enter a critical section, the other processes can wait until it finishes, and then proceed safely.

4.3.3 Protecting Shared State: Locks and Semaphores

All the methods for synchronization and serialization that we will discuss in this section use the same underlying idea. They use variables in shared state as signals that all the processes understand and respect. This is the same philosophy that allows computers in a distributed system to work together -- they coordinate with each other by passing messages according to a protocol that every participant understands and respects.

These mechanisms are not physical barriers that come down to protect shared state. Instead they are based on mutual understanding. It is the same sort of mutual understanding that allows traffic going in multiple directions to safely use an intersection. There are no physical walls that stop cars from crashing into each other, just respect for rules that say red means "stop", and green means "go". Similarly, there is really nothing protecting those shared variables except that the processes are programmed only to access them when a particular signal indicates that it is their turn.

Locks. Locks, also known as mutexes (short for mutual exclusions), are shared objects that are commonly used to signal that shared state is being read or modified. Different programming languages implement locks in different ways, but in Python, a process can try to acquire "ownership" of a lock using the acquire() method, and then release() it some time later when it is done using the shared variables. While a lock is acquired by a process, any other process that tries to perform the acquire() action will automatically be made to wait until the lock becomes free. This way, only one process can acquire a lock at a time.

For a lock to protect a particular set of variables, all the processes need to be programmed to follow a rule: no process will access any of the shared variables unless it owns that particular lock. In effect, all the processes need to "wrap" their manipulation of the shared variables in acquire() and release() statements for that lock.

We can apply this concept to the bank balance example. The critical section in that example was the set of operations starting when balance was read to when balance was written. We saw that problems occurred if more than one process was in this section at the same time. To protect the critical section, we will use a lock. We will call this lock balance_lock (although we could call it anything we liked). In order for the lock to actually protect the section, we must make sure to acquire() the lock before trying to entering the section, and release() the lock afterwards, so that others can have their turn.

>>> from threading import Lock

>>> def make_withdraw(balance):

balance_lock = Lock()

def withdraw(amount):

nonlocal balance

# try to acquire the lock

balance_lock.acquire()

# once successful, enter the critical section

if amount > balance:

print("Insufficient funds")

else:

balance = balance - amount

print(balance)

# upon exiting the critical section, release the lock

balance_lock.release()

If we set up the same situation as before:

w = make_withdraw(10)

And now execute w(8) and w(7) in parallel:

P1 P2

acquire balance_lock: ok

read balance: 10 acquire balance_lock: wait

read amount: 8 wait

8 > 10: False wait

if False wait

10 - 8: 2 wait

write balance -> 2 wait

read balance: 2 wait

print 2 wait

release balance_lock wait

acquire balance_lock:ok

read balance: 2

read amount: 7

7 > 2: True

if True

print 'Insufficient funds'

release balance_lock

We see that it is impossible for two processes to be in the critical section at the same time. The instant one process acquires balancelock, the other one has to wait until that processes _finishes its critical section before it can even start.

Note that the program will not terminate unless P1 releases balance_lock. If it does not release balance_lock, P2 will never be able to acquire it and will be stuck waiting forever. Forgetting to release acquired locks is a common error in parallel programming.

Semaphores. Semaphores are signals used to protect access to limited resources. They are similar to locks, except that they can be acquired multiple times up to a limit. They are like elevators that can only carry a certain number of people. Once the limit has been reached, a process must wait to use the resource until another process releases the semaphore and it can acquire it.

For example, suppose there are many processes that need to read data from a central database server. The server may crash if too many processes access it at once, so it is a good idea to limit the number of connections. If the database can only support N=2 connections at once, we can set up a semaphore with value N=2.

>>> from threading import Semaphore

>>> db_semaphore = Semaphore(2) # set up the semaphore

>>> database = []

>>> def insert(data):

db_semaphore.acquire() # try to acquire the semaphore

database.append(data) # if successful, proceed

db_semaphore.release() # release the semaphore

>>> insert(7)

>>> insert(8)

>>> insert(9)

The semaphore will work as intended if all the processes are programmed to only access the database if they can acquire the semaphore. Once N=2 processes have acquired the semaphore, any other processes will wait until one of them has released the semaphore, and then try to acquire it before accessing the database:

P1 P2 P3

acquire db_semaphore: ok acquire db_semaphore: wait acquire db_semaphore: ok

read data: 7 wait read data: 9

append 7 to database wait append 9 to database

release db_semaphore: ok acquire db_semaphore: ok release db_semaphore: ok

read data: 8

append 8 to database

release db_semaphore: ok

A semaphore with value 1 behaves like a lock.

4.3.4 Staying Synchronized: Condition variables

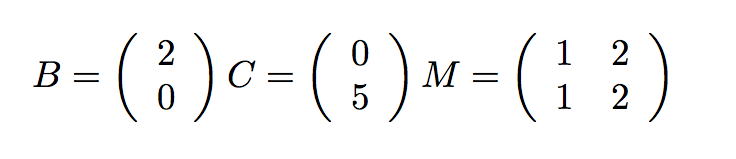

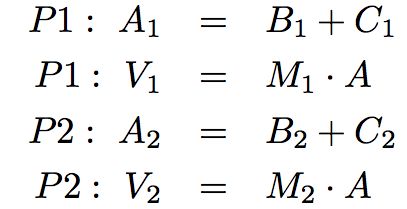

Condition variables are useful when a parallel computation is composed of a series of steps. A process can use a condition variable to signal it has finished its particular step. Then, the other processes that were waiting for the signal can start their work. An example of a computation that needs to proceed in steps a sequence of large-scale vector computations. In computational biology, web-scale computations, and image processing and graphics, it is common to have very large (million-element) vectors and matrices. Imagine the following computation:

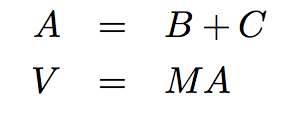

We may choose to parallelize each step by breaking up the matrices and vectors into range of rows, and assigning each range to a separate thread. As an example of the above computation, imagine the following simple values:

We will assign first half (in this case the first row) to one thread, and the second half (second row) to another thread:

In pseudocode, the computation is:

def do_step_1(index):

A[index] = B[index] + C[index]

def do_step_2(index):

V[index] = M[index] . A

Process 1 does:

do_step_1(1)

do_step_2(1)

And process 2 does:

do_step_1(2)

do_step_2(2)

If allowed to proceed without synchronization, the following inconsistencies could result:

P1 P2

read B1: 2

read C1: 0

calculate 2+0: 2

write 2 -> A1 read B2: 0

read M1: (1 2) read C2: 5

read A: (2 0) calculate 5+0: 5

calculate (1 2).(2 0): 2 write 5 -> A2

write 2 -> V1 read M2: (1 2)

read A: (2 5)

calculate (1 2).(2 5):12

write 12 -> V2

The problem is that V should not be computed until all the elements of A have been computed. However, P1 finishes A = B+C and moves on to V = MA before all the elements of A have been computed. It therefore uses an inconsistent value of A when multiplying by M.

We can use a condition variable to solve this problem.

Condition variables are objects that act as signals that a condition has been satisfied. They are commonly used to coordinate processes that need to wait for something to happen before continuing. Processes that need the condition to be satisfied can make themselves wait on a condition variable until some other process modifies it to tell them to proceed.

In Python, any number of processes can signal that they are waiting for a condition using the condition.wait() method. After calling this method, they automatically wait until some other process calls the condition.notify() or condition.notifyAll() function. The notify() method wakes up just one process, and leaves the others waiting. The notifyAll() method wakes up all the waiting processes. Each of these is useful in different situations.

Since condition variables are usually associated with shared variables that determine whether or not the condition is true, they are offer acquire() and release() methods. These methods should be used when modifying variables that could change the status of the condition. Any process wishing to signal a change in the condition must first get access to it using acquire().

In our example, the condition that must be met before advancing to the second step is that both processes must have finished the first step. We can keep track of the number of processes that have finished a step, and whether or not the condition has been met, by introducing the following 2 variables:

step1_finished = 0

start_step2 = Condition()

We will insert a start_step_2().wait() at the beginning of do_step_2. Each process will increment step1_finished when it finishes Step 1, but we will only signal the condition when step_1_finished = 2. The following pseudocode illustrates this:

step1_finished = 0

start_step2 = Condition()

def do_step_1(index):

A[index] = B[index] + C[index]

# access the shared state that determines the condition status

start_step2.acquire()

step1_finished += 1

if(step1_finished == 2): # if the condition is met

start_step2.notifyAll() # send the signal

#release access to shared state

start_step2.release()

def do_step_2(index):

# wait for the condition

start_step2.wait()

V[index] = M[index] . A

With the introduction of this condition, both processes enter Step 2 together as follows::

P1 P2

read B1: 2

read C1: 0

calculate 2+0: 2

write 2 -> A1 read B2: 0

acquire start_step2: ok read C2: 5

write 1 -> step1_finished calculate 5+0: 5

step1_finished == 2: false write 5-> A2

release start_step2: ok acquire start_step2: ok

start_step2: wait write 2-> step1_finished

wait step1_finished == 2: true

wait notifyAll start_step_2: ok

start_step2: ok start_step2:ok

read M1: (1 2) read M2: (1 2)

read A:(2 5)

calculate (1 2). (2 5): 12 read A:(2 5)

write 12->V1 calculate (1 2). (2 5): 12

write 12->V2

Upon entering do_step_2, P1 has to wait on start_step_2 until P2 increments step1_finished, finds that it equals 2, and signals the condition.

4.3.5 Deadlock

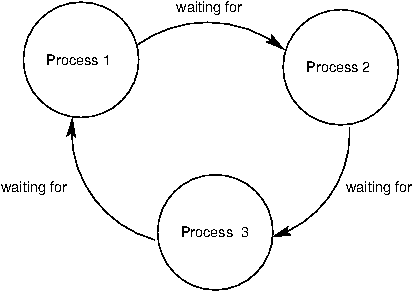

While synchronization methods are effective for protecting shared state, they come with a catch. Because they cause processes to wait on each other, they are vulnerable to deadlock, a situation in which two or more processes are stuck, waiting for each other to finish. We have already mentioned how forgetting to release a lock can cause a process to get stuck indefinitely. But even if there are the correct number of acquire() and release() calls, programs can still reach deadlock.

The source of deadlock is a circular wait, illustrated below. No process can continue because it is waiting for other processes that are waiting for it to complete.

As an example, we will set up a deadlock with two processes. Suppose there are two locks, x_lock and y_lock, and they are used as follows:

>>> x_lock = Lock()

>>> y_lock = Lock()

>>> x = 1

>>> y = 0

>>> def compute():

x_lock.acquire()

y_lock.acquire()

y = x + y

x = x * x

y_lock.release()

x_lock.release()

>>> def anti_compute():

y_lock.acquire()

x_lock.acquire()

y = y - x

x = sqrt(x)

x_lock.release()

y_lock.release()

If compute() and anti_compute() are executed in parallel, and happen to interleave with each other as follows:

P1 P2

acquire x_lock: ok acquire y_lock: ok

acquire y_lock: wait acquire x_lock: wait

wait wait

wait wait

wait wait

... ...

the resulting situation is a deadlock. P1 and P2 are each holding on to one lock, but they need both in order to proceed. P1 is waiting for P2 to release y_lock, and P2 is waiting for P1 to release x_lock. As a result, neither can proceed.