3.6 Interpreters for Languages with Abstraction

The Calculator language provides a means of combination through nested call expressions. However, there is no way to define new operators, give names to values, or express general methods of computation. In summary, Calculator does not support abstraction in any way. As a result, it is not a particularly powerful or general programming language. We now turn to the task of defining a general programming language that supports abstraction by binding names to values and defining new operations.

Rather than extend our simple Calculator language further, we will begin anew and develop an interpreter for the Logo language. Logo is not a language invented for this course, but instead a classic instructional language with dozens of interpreter implementations and its own developer community.

Unlike the previous section, which presented a complete interpreter as Python source code, this section takes a descriptive approach. The companion project asks you to implement the ideas presented here by building a fully functional Logo interpreter.

3.6.1 The Scheme Language

Scheme is a dialect of Lisp, the second-oldest programming language that is still widely used today (after Fortran). Scheme was first described in 1975 by Gerald Sussman and Guy Steele. From the introduction to the Revised(4) Report on the Algorithmic Language Scheme_,

> Programming languages should be designed not by piling feature on top of feature, but by removing the weaknesses and restrictions that make additional features appear necessary. Scheme demonstrates that a very small number of rules for forming expressions, with no restrictions on how they are composed, suffice to form a practical and efficient programming language that is flexible enough to support most of the major programming paradigms in use today.

We refer you to this Report for full details of the Scheme language. We'll touch on highlights here. We've used examples from the Report in the descriptions below..

Despite its simplicity, Scheme is a real programming language and in many ways is similar to Python, but with a minimum of "syntactic sugar"[1]. Basically, all operations take the form of function calls. Here, we will describe a representative subset of the full Scheme language described in the report.

| [1] | Regrettably, this has become less true in more recent revisions of the Scheme language, such as the Revised(6) Report, so here, we'll stick with previous versions. |

There are several implementations of Scheme available, which add on various additional procedures. At Berkeley, we've used a modified version of the Stk interpreter, which is also available as stk on our instructional servers. Unfortunately, it is not particularly conformant to the official specification, but it will do for our purposes.

Using the Interpreter. As with the Python interpreter[#], expressions typed to the Stk interpreter are evaluated and printed by what is known as a read-eval-print loop:

>>> 3

3

>>> (- (/ (* (+ 3 7 10) (- 1000 8)) 992) 17)

3

>>> (define (fib n) (if (< n 2) n (+ (fib (- n 2)) (fib (- n 1)))))

fib

>>> '(1 (7 19))

(1 (7 19))

| [2] | In our examples, we use the same notation as for Python: >>> and ... to indicate lines input to the interpreter and unprefixed lines to indicate output. In reality, Scheme interpreters use different prompts. STk, for example, prompts with STk> and does not prompt for continuation lines. The Python conventions, however, make it clearer what is input and what is output. |

Values in Scheme. Values in Scheme generally have their counterparts in Python.

> Booleans

>

> The values true and false, denoted #t and #f. In Scheme, the only false value (in the Python sense) is #f.

>

> Numbers

>

> These include integers of arbitrary precision, rational numbers, complex numbers, and "inexact" (generally floating-point) numbers. Integers may be denoted either in standard decimal notation or in other radixes by prefixing a numeral with #o (octal), #x (hexadecimal), or #b (binary).

>

> Symbols

>

> Symbols are a kind of string, but are denoted without quotation marks. The valid characters include letters, digits, and:

>

> > ! $ % & * / : < = > ? ^ _ ~ + - . @

>

>

>

> When input by the read function, which reads Scheme expressions (and which the interpreter uses to input program text), upper and lower case characters in symbols are not distinguished (in the STk implementation, converted to lower case). Two symbols with the same denotation denote the same object (not just two objects that happen to have the same contents).

>

> Pairs and Lists

>

> A pair is an object containing two components (of any types), called its car and cdr. A pair whose car is A and whose cdr is B is denoted (A . B). Pairs (like tuples in Python) can represent lists, trees, and arbitrary hierarchical structures.

>

> A standard Scheme list consists either of the special empty list value (denoted ()), or of a pair that contains the first item of the list as its car and the rest of the list as its cdr. Thus, the list consisting of the integers 1, 2, and 3 would be represented:

>

> > (1 . (2 . (3 . ())))

>

>

>

> Lists are so pervasive that Scheme allows one to abbreviate (a . ()) as (a), and allows one to abbreviate (a . (b ...)) as (a b ...). Thus, the list above is usually written:

>

> > (1 2 3)

>

>

>

> Procedures (functions)

>

> As in Python, a procedure (or function) value represents some computation that can be invoked by a function call supplying argument values. Procedures may either be primitives, supplied by the Scheme runtime system, or they may be constructed out of Scheme expression(s) and an environment (exactly as in Python). There is no direct denotation for function values, although there are predefined identifiers that are bound to primitive functions and there are Scheme expressions that, when evaluated, produce new procedure values.

>

> Other Types

>

> Scheme also supports characters and strings (like Python strings, except that Scheme distinguishes characters from strings), and vectors (like Python lists).

Program Denotations As with other versions of Lisp, Scheme's data values double as representations of programs. For example, the Scheme list:

(+ x (* 10 y))

can, depending on how it is used, represent either a 3-item list (whose last item is also a 3-item list), or it can represent a Scheme expression for computing (x+10y). To interpret a Scheme value as a program, we consider the type of value, and evaluate as follows:

> Integers, booleans, characters, strings, and vectors evaluate to themselves. Thus, the expression 5 evaluates to 5.

> Bare symbols serve as variables. Their values are determined by the current environment in which they are being evaluated, just as in Python.

> Non-empty lists are interpreted in two different ways, depending on their first component:

> If the first component is one of the symbols denoting a special form, described below, the evaluation proceeds by the rules for that special form.

> In all other cases (called combinations), the items in the list are evaluated (recursively) in some unspecified order. The value of the first item must be a function value. That value is called, with the values of the remaining items in the list supplying the arguments.

> Other Scheme values (in particular, pairs that are not lists) are erroneous as programs.

For example:

>>> 5 ; A literal.

5

>>> (define x 3) ; A special form that creates a binding for symbol

x ; x.

>>> (+ 3 (* 10 x)) ; A combination. Symbol + is bound to the primitive

33 ; add function and * to primitive multiply.

Primitive Special Forms. The special forms denote things such as control structures, function definitions, or class definitions in Python: constructs in which the operands are not simply evaluated immediately, as they are in calls.

First, a couple of common constructs used in the forms:

> EXPR-SEQ

>

> Simply a sequence of expressions, such as:

>

> > (+ 3 2) x (* y z)

>

>

>

> When this appears in the definitions below, it refers to a sequence of expressions that are evaluated from left to right, with the value of the sequence (if needed) being the value of the last expression.

>

> BODY

>

> Several constructs have "bodies", which are EXPR-SEQ_s, as above, optionally preceded by one or more Definitions. Their value is that of their _EXPR-SEQ. See the section on Internal Definitions for the interpretation of these definitions.

Here is a representative subset of the special forms:

> Definitions

>

> Definitions may appear either at the top level of a program (that is, not enclosed in another construct).

>

> > (define SYM EXPR)

> >

> > This evaluates EXPR and binds its value to the symbol SYM in the current environment.

> >

> > (define (SYM ARGUMENTS) BODY)

> >

> > This is equivalent to

> >

> > > (define SYM (lambda (ARGUMENTS) BODY))

>

> (lambda (ARGUMENTS) BODY)

>

> This evaluates to a function. ARGUMENTS is usually a list (possibly empty) of distinct symbols that gives names to the arguments of the function, and indicates their number. It is also possible for ARGUMENTS to have the form:

>

> > (sym1 sym2 ... symn . symr)

>

>

>

> (that is, instead of ending in the empty list like a normal list, the last cdr is a symbol). In this case, symr will be bound to the list of trailing argument values (argument n+1 onward).

>

> When the resulting function is called, ARGUMENTS are bound to the argument values in a fresh environment frame that extends the environment in which the lambda expression was evaluated (just like Python). Then the BODY is evaluated and its value returned as the value of the call.

>

> (if COND-EXPR TRUE-EXPR OPTIONAL-FALSE-EXPR)

>

> Evaluates COND-EXPR, and if its value is not #f, then evaluates TRUE-EXPR, and the result is the value of the if. If COND-EXPR evaluates to #f and OPTIONAL-FALSE-EXPR is present, it is evaluated and its result is the value of the if. If it is absent, the value of the if is unspecified.

>

> (set! SYMBOL EXPR)

>

> Evaluates EXPR and replaces the binding of SYMBOL with the resulting value. SYMBOL must be bound, or there is an error. In contrast to Python's default, this replaces the binding of SYMBOL in the first enclosing environment frame that defines it, which is not always the innermost frame.

>

> (quote EXPR) or 'EXPR

>

> One problem with using Scheme data structures as program representations is that one needs a way to indicate when a particular symbol or list represents literal data to be manipulated by a program, and when it is program text that is intended to be evaluated. The quote form evaluates to EXPR itself, without further evaluating EXPR. (The alternative form, with leading apostrophe, gets converted to the first form by Scheme's expression reader.) For example:

>

> > >>> (+ 1 2)

> 3

> >>> '(+ 1 2)

> (+ 1 2)

> >>> (define x 3)

> x

> >>> x

> 3

> >>> (quote x)

> x

> >>> '5

> 5

> >>> (quote 'x)

> (quote x)

>

>

Derived Special Forms

A derived construct is one that can be translated into primitive constructs. Their purpose is to make programs more concise or clear for the reader. In Scheme, we have

> (begin EXPR-SEQ)

>

> Simply evaluates and yields the value of the EXPR-SEQ. This construct is simply a way to execute a sequence of expressions in a context (such as an if) that requires a single expression.

>

> (and EXPR1 EXPR2 ...)

>

> Each EXPR is evaluated from left to right until one returns #f or the EXPR_s are exhausted. The value is that of the last _EXPR evaluated, or #t if the list of EXPR_s is empty. For example:

>

> > >>> (and (= 2 2) (> 2 1))

> #t

> >>> (and (< 2 2) (> 2 1))

> #f

> >>> (and (= 2 2) '(a b))

> (a b)

> >>> (and)

> #t

>

>

>

> (or _EXPR1 EXPR2 ...)

>

> Each EXPR is evaluated from left to right until one returns a value other than #f or the EXPR_s are exhausted. The value is that of the last _EXPR evaluated, or #f if the list of EXPR_s is empty: For example:

>

> > >>> (or (= 2 2) (> 2 3))

> #t

> >>> (or (= 2 2) '(a b))

> #t

> >>> (or (> 2 2) '(a b))

> (a b)

> >>> (or (> 2 2) (> 2 3))

> #f

> >>> (or)

> #f

>

>

>

> (cond _CLAUSE1 CLAUSE2 ...)

>

> Each CLAUSEi is processed in turn until one succeeds, and its value becomes the value of the cond. If no clause succeeds, the value is unspecified. Each clause has one of three possible forms. The form

>

> > (TEST-EXPR EXPR-SEQ)

>

> succeeds if TEST-EXPR evaluates to a value other than #f. In that case, it evaluates EXPR-SEQ and yields its value. The EXPR-SEQ may be omitted, in which case the value is that of TEST-EXPR itself.

>

> The last clause may have the form

>

> > (else EXPR-SEQ)

>

> which is equivalent to

>

> > (#t EXPR-SEQ)

>

> Finally, the form

>

> > (TEST_EXPR => EXPR)

>

> succeeds if TEST_EXPR evaluates to a value other than #f, call it V. If it succeeds, the value of the cond construct is that returned by (EXPR V). That is, EXPR must evaluate to a one-argument function, which is applied to the value of TEST_EXPR.

>

> For example:

>

> > >>> (cond ((> 3 2) 'greater)

> ... ((< 3 2) 'less)))

> greater

> >>> (cond ((> 3 3) 'greater)

> ... ((< 3 3) 'less)

> ... (else 'equal))

> equal

> >>> (cond ((if (< -2 -3) #f -3) => abs)

> ... (else #f))

> 3

>

>

>

> (case KEY-EXPR CLAUSE1 CLAUSE2 ...)

>

> Evaluates KEY-EXPR to produce a value, K. Then matches K against each CLAUSE1 in turn until one succeeds, and returns the value of that clause. If no clause succeeds, the value is unspecified. Each clause has the form

>

> > ((DATUM1 DATUM2 ...) EXPR-SEQ)

>

> The DATUM_s are Scheme values (they are _not evaluated). The clause succeeds if K matches one of the DATUM values (as determined by the eqv? function described below.) If the clause succeeds, its EXPR-SEQ is evaluated and its value becomes the value of the case. The last clause may have the form

>

> > (else EXPR-SEQ)

>

> which always succeeds. For example:

>

> > >>> (case (* 2 3)

> ... ((2 3 5 7) 'prime)

> ... ((1 4 6 8 9) 'composite))

> composite

> >>> (case (car '(a . b))

> ... ((a c) 'd)

> ... ((b 3) 'e))

> d

> >>> (case (car '(c d))

> ... ((a e i o u) 'vowel)

> ... ((w y) 'semivowel)

> ... (else 'consonant))

> consonant

>

>

>

> (let BINDINGS BODY)

>

> BINDINGS is a list of pairs of the form

>

> > ( (VAR1 INIT1) (VAR2 INIT2) ...)

>

> where the VAR_s are (distinct) symbols and the _INIT_s are expressions. This first evaluates the _INIT expressions, then creates a new frame that binds those values to the VAR_s, and then evaluates the _BODY in that new environment, returning its value. In other words, this is equivalent to the call

>

> > ((lambda (VAR1 VAR2 ...) BODY)INIT1 INIT2 ...)

>

> Thus, any references to the VAR_s in the _INIT expressions refers to the definitions (if any) of those symbols outside of the let construct. For example:

>

> > >>> (let ((x 2) (y 3))

> ... (* x y))

> 6

> >>> (let ((x 2) (y 3))

> ... (let ((x 7) (z (+ x y)))

> ... (* z x)))

> 35

>

>

>

> (let BINDINGS BODY)

>

> The syntax of BINDINGS is the same as for let. This is equivalent to

>

> > (let ((VAR1 INIT1))...(let ((VARn INITn))BODY))

>

> In other words, it is like let except that the new binding of VAR1 is visible in subsequent INIT_s as well as in the _BODY, and similarly for VAR2. For example:

>

> ```

> >>> (define x 3)

> x

> >>> (define y 4)

> y

> >>> (let ((x 5) (y (+ x 1))) y)

> 4

> >>> (let ((x 5) (y (+ x 1))) y)

> 6

>

> >

> (letrec _BINDINGS_ _BODY_)

>

> Again, the syntax is as for `let`. In this case, the new bindings are all created first (with undefined values) and then the _INIT_s are evaluated and assigned to them. It is undefined what happens if one of the _INIT_s uses the value of a _VAR_ that has not had an initial value assigned yet. This form is intended mostly for defining mutually recursive functions (lambdas do not, by themselves, use the values of the variables they mention; that only happens later, when they are called. For example:

>

>

> (letrec ((even?

> (lambda (n)

> (if (zero? n)

> #t

> (odd? (- n 1)))))

> (odd?

> (lambda (n)

> (if (zero? n)

> #f

> (even? (- n 1))))))

> (even? 88))

>

> ```

Internal Definitions. When a BODY begins with a sequence of define constructs, they are known as "internal definitions" and are interpreted a little differently from top-level definitions. Specifically, they work like letrec does.

> First, bindings are created for all the names defined by the define statements, initially bound to undefined values.

> Then the values are filled in by the defines.

As a result, a sequence of internal function definitions can be mutually recursive, just as def statements in Python that are nested inside a function can be:

>>> (define (hard-even? x) ;; An outer-level definition

... (define (even? n) ;; Inner definition

... (if (zero? n)

... #t

... (odd? (- n 1))))

... (define (odd? n) ;; Inner definition

... (if (zero? n)

... #f

... (even? (- n 1))))

... (even? x))

>>> (hard-even? 22)

#t

Predefined Functions. There is a large collection of predefined functions, all bound to names in the global environment, and we'll simply illustrate a few here; the rest are catalogued in the Revised(4) Scheme Report. Function calls are not "special" in that they all use the same completely uniform evaluation rule: recursively evaluate all items (including the operator), and then apply the operator's value (which must be a function) to the operands' values.

> Arithmetic: Scheme provides the standard arithmetic operators, many with familiar denotations, although the operators uniformly appear before the operands:

>

>

>

> ```

> >>> ; Semicolons introduce one-line comments.

> >>> ; Compute (3+7+10)(1000-8) // 992 - 17

> >>> (- (quotient ( (+ 3 7 10) (- 1000 8))) 17)

> 3

> >>> (remainder 27 4)

> 3

> >>> (- 17)

> -17

>

> >

>

>

> Similarly, there are the usual numeric comparison operators, extended to allow more than two operands:

>

>

>

> >

> > >>> (< 0 5)

> > #t

> > >>> (>= 100 10 10 0)

> > #t

> > >>> (= 21 ( 7 3) (+ 19 2))

> > #t

> > >>> (not (= 15 14))

> > #t

> > >>> (zero? (- 7 7))

> > #t

> >

> > >

>

>

> `not`, by the way, is a function, not a special form like `and` or `or`, because its operand must always be evaluated, and so needs no special treatment.

>

>

> * **Lists and Pairs:** A large number of operations deal with pairs and lists (which again are built of pairs and empty lists):

>

>

>

>

> >>> (cons 'a 'b)

> (a . b)

> >>> (list 'a 'b)

> (a b)

> >>> (cons 'a (cons 'b '()))

> (a b)

> >>> (car (cons 'a 'b))

> a

> >>> (cdr (cons 'a 'b))

> b

> >>> (cdr (list a b))

> (b)

> >>> (cadr '(a b)) ; An abbreviation for (car (cdr '(a b)))

> b

> >>> (cddr '(a b)) ; Similarly, an abbreviation for (cdr (cdr '(a b)))

> ()

> >>> (list-tail '(a b c) 0)

> (a b c)

> >>> (list-tail '(a b c) 1)

> (b c)

> >>> (list-ref '(a b c) 0)

> a

> >>> (list-ref '(a b c) 2)

> c

> >>> (append '(a b) '(c d) '() '(e))

> (a b c d e)

> >>> ; All but the last list is copied. The last is shared, so:

> >>> (define L1 (list 'a 'b 'c))

> >>> (define L2 (list 'd))

> >>> (define L3 (append L1 L2))

> >>> (set-car! L1 1)

> >>> (set-car! L2 2)

> >>> L3

> (a b c 2)

> >>> (null? '())

> #t

> >>> (list? '())

> #t

> >>> (list? '(a b))

> #t

> >>> (list? '(a . b))

> #f

>

> >

>

> * **Equivalence:** The `=` operation is for numbers. For general equality of values, Scheme distinguishes `eq?` (like Python's `is`), `eqv?` (similar, but is the same as `=` on numbers), and `equal?` (compares list structures and strings for content). Generally, we use `eqv?` or `equal?`, except in cases such as comparing symbols, booleans, or the null list:

>

>

>

>

> >>> (eqv? 'a 'a)

> #t

> >>> (eqv? 'a 'b)

> #f

> >>> (eqv? 100 (+ 50 50))

> #t

> >>> (eqv? (list 'a 'b) (list 'a 'b))

> #f

> >>> (equal? (list 'a 'b) (list 'a 'b))

> #t

>

> >

>

> * **Types:** Each type of value satisfies exactly one of the basic type predicates:

>

>

>

>

> >>> (boolean? #f)

> #t

> >>> (integer? 3)

> #t

> >>> (pair? '(a b))

> #t

> >>> (null? '())

> #t

> >>> (symbol? 'a)

> #t

> >>> (procedure? +)

> #t

>

> >

>

> * **Input and Output:** Scheme interpreters typically run a read-eval-print loop, but one can also output things under explicit control of the program, using the same functions the interpreter does internally:

>

>

>

>

> >>> (begin (display 'a) (display 'b) (newline))

> ab

>

> >

>

>

> Thus, `(display x)` is somewhat akin to Python's

>

>

>

> > `print(str(x), end="")`

>

>

>

> and `(newline)` is like `print()`.

>

>

>

> For input, the `(read)` function reads a Scheme expression from the current "port". It does _not_ interpret the expression, but rather reads it as data:

>

>

>

>

> >>> (read)

> >>> (a b c)

> (a b c)

>

> >

>

> * **Evaluation:** The `apply` function provides direct access to the function-calling operation:

>

>

>

> >

> > >>> (apply cons '(1 2))

> > (1 . 2)

> > >>> ;; Apply the function f to the arguments in L after g is

> > >>> ;; applied to each of them

> > >>> (define (compose-list f g L)

> > ... (apply f (map g L)))

> > >>> (compose-list + (lambda (x) (* x x)) '(1 2 3))

> > 14

> >

> > >

>

>

> An extension allows for some "fixed" arguments at the beginning:

>

>

>

> >

> > >>> (apply + 1 2 '(3 4 5))

> > 15

> >

> > >

>

>

> The following function is not in [Revised(4) Scheme](http://people.csail.mit.edu/jaffer/r4rs_toc.html), but is present in our versions of the interpreter (_warning:_ a non-standard procedure that is not defined this way in later versions of Scheme):

>

>

>

>

> >>> (eval '(+ 1 2))

> 3

>

> >

>

>

> That is, `eval` evaluates a piece of Scheme data that represents a correct Scheme expression. This version evaluates its expression argument in the global environment. Our interpreter also provides a way to specify a specific environment for the evaluation:

>

>

>

> >

> > >>> (define (incr n) (lambda (x) (+ n x)))

> > >>> (define add5 (incr 5))

> > >>> (add5 13)

> > 18

> > >>> (eval 'n (procedure-environment add5))

> > 5

> >

> > ```

3.6.2 The Logo Language

Logo is another dialect of Lisp. It was designed for educational use, and so many design decisions in Logo are meant to make the language more comfortable for a beginner. For example, most Logo procedures are invoked in prefix form (first the procedure name, then the arguments), but the common arithmetic operators are also provided in the customary infix form. The brilliance of Logo is that its simple, approachable syntax still provides amazing expressivity for advanced programmers.

The central idea in Logo that accounts for its expressivity is that its built-in container type, the Logo sentence (also called a list), can easily store Logo source code! Logo programs can write and interpret Logo expressions as part of their evaluation process. Many dynamic languages support code generation, including Python, but no language makes code generation quite as fun and accessible as Logo.

You may want to download a fully implemented Logo interpreter at this point to experiment with the language. The standard implementation is Berkeley Logo (also known as UCBLogo), developed by Brian Harvey and his Berkeley students. For macintosh uses, ACSLogo is compatible with the latest version of Mac OSX and comes with a user guide that introduces many features of the Logo language.

Fundamentals. Logo is designed to be conversational. The prompt of its read-eval loop is a question mark (?), evoking the question, "what shall I do next?" A natural starting point is to ask Logo to print a number:

? print 5

5

The Logo language employs an unusual call expression syntax that has no delimiting punctuation at all. Above, the argument 5 is passed to print, which prints out its argument. The terminology used to describe the programming constructs of Logo differs somewhat from that of Python. Logo has procedures rather than the equivalent "functions" in Python, and procedures output values rather than "returning" them. The print procedure always outputs None, but prints a string representation of its argument as a side effect. (Procedure arguments are typically called inputs in Logo, but we will continue to call them arguments in this text for the sake of clarity.)

The most common data type in Logo is a word, a string without spaces. Words serve as general-purpose values that can represent numbers, names, and boolean values. Tokens that can be interpreted as numbers or boolean values, such as 5, evaluate to words directly. On the other hand, names such as five are interpreted as procedure calls:

? 5

You do not say what to do with 5.

? five

I do not know how to five.

While 5 and five are interpreted differently, the Logo read-eval loop complains either way. The issue with the first case is that Logo complains whenever a top-level expression it evaluates does not evaluate to None. Here, we see the first structural difference between the interpreters for Logo and Calculator; the interface to the former is a read-eval loop that expects the user to print results. The latter employed a more typical read-eval-print loop that printed return values automatically. Python takes a hybrid approach: only non-None values are coerced to strings using repr and then printed automatically.

A line of Logo can contain multiple expressions in sequence. The interpreter will evaluate each one in turn. It will complain if any top-level expression in a line does not evaluate to None. Once an error occurs, the rest of the line is ignored:

? print 1 print 2

1

2

? 3 print 4

You do not say what to do with 3.

Logo call expressions can be nested. In the version of Logo we will implement, each procedure takes a fixed number of arguments. Therefore, the Logo interpreter is able to determine uniquely when the operands of a nested call expression are complete. Consider, for instance, two procedures sum and difference that output the sum and difference of their two arguments, respectively:

? print sum 10 difference 7 3

14

We can see from this nesting example that the parentheses and commas that delimit call expressions are not strictly necessary. In the Calculator interpreter, punctuation allowed us to build expression trees as a purely syntactic operation; without ever consulting the meaning of the operator names. In Logo, we must use our knowledge of how many arguments each procedure takes in order to discover the correct structure of a nested expression. This issue is addressed in further detail in the next section.

Logo also supports infix operators, such as + and *. The precedence of these operators is resolved according to the standard rules of algebra; multiplication and division take precedence over addition and subtraction:

? 2 + 3 * 4

14

The details of how to implement operator precedence and infix operators to form correct expression trees is left as an exercise. For the following discussion, we will concentrate on call expressions using prefix syntax.

Quotation. A bare name is interpreted as the beginning of a call expression, but we would also like to reference words as data. A token that begins with a double quote is interpreted as a word literal. Note that word literals do not have a trailing quotation mark in Logo:

? print "hello

hello

In dialects of Lisp (and Logo is such a dialect), any expression that is not evaluated is said to be quoted. This notion of quotation is derived from a classic philosophical distinction between a thing, such as a dog, which runs around and barks, and the word "dog" that is a linguistic construct for designating such things. When we use "dog" in quotation marks, we do not refer to some dog in particular but instead to a word. In language, quotation allow us to talk about language itself, and so it is in Logo. We can refer to the procedure for sum by name without actually applying it by quoting it:

? print "sum

sum

In addition to words, Logo includes the sentence type, interchangeably called a list. Sentences are enclosed in square brackets. The print procedure does not show brackets to preserve the conversational style of Logo, but the square brackets can be printed in the output by using the show procedure:

? print [hello world]

hello world

? show [hello world]

[hello world]

Sentences can be constructed using three different two-argument procedures. The sentence procedure combines its arguments into a sentence. It is polymorphic; it places its arguments into a new sentence if they are words or concatenates its arguments if they are sentences. The result is always a sentence:

? show sentence 1 2

[1 2]

? show sentence 1 [2 3]

[1 2 3]

? show sentence [1 2] 3

[1 2 3]

? show sentence [1 2] [3 4]

[1 2 3 4]

The list procedure creates a sentence from two elements, which allows the user to create hierarchical data structures:

? show list 1 2

[1 2]

? show list 1 [2 3]

[1 [2 3]]

? show list [1 2] 3

[[1 2] 3]

? show list [1 2] [3 4]

[[1 2] [3 4]]

Finally, the fput procedure creates a list from a first element and the rest of the list, as did the Rlist Python constructor from earlier in the chapter:

? show fput 1 [2 3]

[1 2 3]

? show fput [1 2] [3 4]

[[1 2] 3 4]

Collectively, we can call sentence, list, and fput the sentence constructors in Logo. Deconstructing a sentence into its first, last, and rest (called butfirst) in Logo is straightforward as well. Hence, we also have a set of selector procedures for sentences:

? print first [1 2 3]

1

? print last [1 2 3]

3

? print butfirst [1 2 3]

[2 3]

Expressions as Data. The contents of a sentence is also quoted in the sense that it is not evaluated. Hence, we can print Logo expressions without evaluating them:

? show [print sum 1 2]

[print sum 1 2]

The purpose of representing Logo expressions as sentences is typically not to print them out, but instead to evaluate them using the run procedure:

? run [print sum 1 2]

3

Combining quotation, sentence constructors, and the run procedure, we arrive at a very general means of combination that builds Logo expressions on the fly and then evaluates them:

? run sentence "print [sum 1 2]

3

? print run sentence "sum sentence 10 run [difference 7 3]

14

The point of this last example is to show that while the procedures sum and difference are not first-class constructs in Logo (they cannot be placed in a sentence, for instance), their quoted names are first-class, and the run procedure can resolve those names to the procedures to which they refer.

The ability to represent code as data and later interpret it as part of the program is a defining feature of Lisp-style languages. The idea that a program can rewrite itself as it executes is a powerful one, and served as the foundation for early research in artificial intelligence (AI). Lisp was the preferred language of AI researchers for decades. The Lisp language was invented by John McCarthy, who coined the term "artificial intelligence" and played a critical role in defining the field. This code-as-data property of Lisp dialects, along with their simplicity and elegance, continues to attract new Lisp programmers today.

Turtle graphics. No implementation of Logo is complete without graphical output based on the Logo turtle. This turtle begins in the center of a canvas, moves and turns based on procedures, and draws lines behind it as it moves. While the turtle was invented to engage children in the act of programming, it remains an entertaining graphical tool for even advanced programmers.

At any moment during the course of executing a Logo program, the Logo turtle has a position and heading on the canvas. Single-argument procedures such as forward and right change the position and heading of the turtle. Common procedures have abbreviations: forward can also be called as fd, etc. The nested expression below draws a star with a smaller star at each vertex:

? repeat 5 [fd 100 repeat 5 [fd 20 rt 144] rt 144]

The full repertoire of Turtle procedures is also built into Python as the turtle library module. A limited subset of these functions are exposed as Logo procedures in the companion project to this chapter.

Assignment. Logo supports binding names to values. As in Python, a Logo environment consists of a sequence of frames, and each frame can have at most one value bound to a given name. In Logo, names are bound with the make procedure, which takes as arguments a name and a value:

? make "x 2

The first argument is the name x, rather than the output of applying the procedure x, and so it must be quoted. The values bound to names are retrieved by evaluating expressions that begin with a colon:

? print :x

2

Any word that begins with a colon, such as :x, is called a variable. A variable evaluates to the value to which the name of the variable is bound in the current environment.

The make procedure does not have the same effect as an assignment statement in Python. The name passed to make is either already bound to a value or is currently unbound.

- If the name is already bound,

makere-binds that name in the first frame in which it is found. - If the name is not bound,

makebinds the name in the global frame.

This behavior contrasts sharply with the semantics of the Python assignment statement, which always binds a name to a value in the first frame of the current environment. The first assignment rule above is similar to Python assignment following a nonlocal statement. The second is similar to Python assignment following a global statement.

Procedures. Logo supports user-defined procedures using definitions that begin with the to keyword. Definitions are the final type of expression in Logo, along with call expressions, primitive expressions, and quoted expressions. The first line of a definition gives the name of the new procedure, followed by the formal parameters as variables. The lines that follow constitute the body of the procedure, which can span multiple lines and must end with a line that contains only the token end. The Logo read-eval loop prompts the user for procedure bodies with a > continuation symbol. Values are output from a user-defined procedure using the output procedure:

? to double :x

> output sum :x :x

> end

? print double 4

8

Logo's application process for a user-defined procedure is similar to the process in Python. Applying a procedure to a sequence of arguments begins by extending an environment with a new frame, binding the formal parameters of the procedure to the argument values, and then evaluating the lines of the body of the procedure in the environment that starts with that new frame.

A call to output has the same role in Logo as a return statement in Python: it halts the execution of the body of a procedure and returns a value. A Logo procedure can return no value at all by calling stop:

? to count

> print 1

> print 2

> stop

> print 3

> end

? count

1

2

Scope. Logo is a dynamically scoped language. A lexically scoped language such as Python does not allow the local names of one function to affect the evaluation of another function unless the second function was explicitly defined within the first. The formal parameters of two top-level functions are completely isolated. In a dynamically scoped language, there is no such isolation. When one function calls another function, the names bound in the local frame for the first are accessible in the body of the second:

? to print_last_x

> print :x

> end

? to print_x :x

> print_last_x

> end

? print_x 5

5

While the name x is not bound in the global frame, it is bound in the local frame for print_x, the function that is called first. Logo's dynamic scoping rules allow the function print_last_x to refer to x, which was bound as the formal parameter of print_x.

Dynamic scoping is implemented by a single change to the environment model of computation. The frame that is created by calling a user-defined function always extends the current environment. For example, the call to print_x above introduces a new frame that extends the current environment, which consists solely of the global frame. Within the body of print_x, the call to print_last_x introduces another frame that extends the current environment, which includes both the local frame for print_x and the global frame. As a result, looking up the name x in the body of print_last_x finds that name bound to 5 in the local frame for print_x. Alternatively, under the lexical scoping rules of Python, the frame for print_last_x would have extended only the global frame and not the local frame for print_x.

A dynamically scoped language has the advantage that its procedures may not need to take as many arguments. For instance, the print_last_x procedure above takes no arguments, and yet its behavior can be parameterized by an enclosing scope.

General programming. Our tour of Logo is complete, and yet we have not introduced any advanced features, such as an object system, higher-order procedures, or even statements. Learning to program effectively in Logo requires piecing together the simple features of the language into effective combinations.

There is no conditional expression type in Logo; the procedures if and ifelse are applied using call expression evaluation rules. The first argument of if is a boolean word, either True or False. The second argument is not an output value, but instead a sentence that contains the line of Logo code to be evaluated if the first argument is True. An important consequence of this design is that the contents of the second argument is not evaluated at all unless it will be used:

? 1/0

div raised a ZeroDivisionError: division by zero

? to reciprocal :x

> if not :x = 0 [output 1 / :x]

> output "infinity

> end

? print reciprocal 2

0.5

? print reciprocal 0

infinity

Not only does the Logo conditional expression not require a special syntax, but it can in fact be implemented in terms of word and run. The primitive procedure ifelse takes three arguments: a boolean word, a sentence to be evaluated if that word is True, and a sentence to be evaluated if that word is False. By clever naming of the formal parameters, we can implement a user-defined procedure ifelse2 with the same behavior:

? to ifelse2 :predicate :True :False

> output run run word ": :predicate

> end

? print ifelse2 emptyp [] ["empty] ["full]

empty

Recursive procedures do not require any special syntax, and they can be used with run, sentence, first, and butfirst to define general sequence operations on sentences. For instance, we can apply a procedure to an argument by building a two-element sentence and running it. The argument must be quoted if it is a word:

? to apply_fn :fn :arg

> output run list :fn ifelse word? :arg [word "" :arg] [:arg]

> end

Next, we can define a procedure for mapping a procedure :fn over the words in a sentence :s incrementally:

? to map_fn :fn :s

> if emptyp :s [output []]

> output fput apply_fn :fn first :s map_fn :fn butfirst :s

> end

? show map "double [1 2 3]

[2 4 6]

The second line of the body of map_fn can also be written with parentheses to indicate the nested structure of the call expression. However, parentheses show where call expressions begin and end, rather than surrounding only the operands and not the operator:

> (output (fput (apply_fn :fn (first :s)) (map_fn :fn (butfirst :s))))

Parentheses are not necessary in Logo, but they often assist programmers in documenting the structure of nested expressions. Most dialects of Lisp require parentheses and therefore have a syntax with explicit nesting.

As a final example, Logo can express recursive drawings using its turtle graphics in a remarkably compact form. Sierpinski's triangle is a fractal that draws each triangle as three neighboring triangles that have vertexes at the midpoints of the legs of the triangle that contains them. It can be drawn to a finite recursive depth by this Logo program:

? to triangle :exp

> repeat 3 [run :exp lt 120]

> end

? to sierpinski :d :k

> triangle [ifelse :k = 1 [fd :d] [leg :d :k]]

> end

? to leg :d :k

> sierpinski :d / 2 :k - 1

> penup fd :d pendown

> end

The triangle procedure is a general method for repeating a drawing procedure three times with a left turn following each repetition. The sierpinski procedure takes a length and a recursive depth. It draws a plain triangle if the depth is 1, and otherwise draws a triangle made up of calls to leg. The leg procedure draws a single leg of a recursive Sierpinski triangle by a recursive call to sierpinski that fills the first half of the length of the leg, then by moving the turtle to the next vertex. The procedures up and down stop the turtle from drawing as it moves by lifting its pen up and the placing it down again. The mutual recursion between sierpinski and leg yields this result:

? sierpinski 400 6

3.6.3 Structure

This section describes the general structure of a Logo interpreter. While this chapter is self-contained, it does reference the companion project. Completing that project will produce a working implementation of the interpreter sketch described here.

An interpreter for Logo can share much of the same structure as the Calculator interpreter. A parser produces an expression data structure that is interpreted by an evaluator. The evaluation function inspects the form of an expression, and for call expressions it calls a function to apply a procedure to some arguments. However, there are structural differences that accommodate Logo's unusual syntax.

Lines. The Logo parser does not read a single expression, but instead reads a full line of code that may contain multiple expressions in sequence. Rather than returning an expression tree, it returns a Logo sentence.

The parser actually does very little syntactic analysis. In particular, parsing does not differentiate the operator and operand subexpressions of call expressions into different branches of a tree. Instead, the components of a call expression are listed in sequence, and nested call expressions are represented as a flat sequence of tokens. Finally, parsing does not determine the type of even primitive expressions such as numbers because Logo does not have a rich type system; instead, every element is a word or a sentence.

>>> parse_line('print sum 10 difference 7 3')

['print', 'sum', '10', 'difference', '7', '3']

The parser performs so little analysis because the dynamic character of Logo requires that the evaluator resolve the structure of nested expressions.

The parser does identify the nested structure of sentences. Sentences within sentences are represented as nested Python lists.

>>> parse_line('print sentence "this [is a [deep] list]')

['print', 'sentence', '"this', ['is', 'a', ['deep'], 'list']]

A complete implementation of parse_line appears in the companion projects as logo_parser.py.

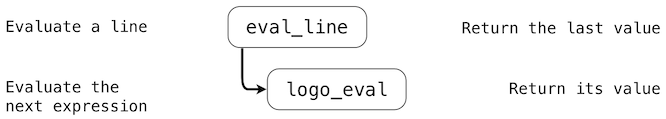

Evaluation. Logo is evaluated one line at a time. A skeleton implementation of the evaluator is defined in logo.py of the companion project. The sentence returned from parse_line is passed to the eval_line function, which evaluates each expression in the line. The eval_line function repeatedly calls logo_eval, which evaluates the next full expression in the line until the line has been evaluated completely, then returns the last value. The logo_eval function evaluates a single expression.

The logo_eval function evaluates the different forms of expressions that we introduced in the last section: primitives, variables, definitions, quoted expressions, and call expressions. The form of a multi-element expression in Logo can be determined by inspecting its first element. Each form of expression as its own evaluation rule.

- A primitive expression (a word that can be interpreted as a number,

True, orFalse) evaluates to itself. - A variable is looked up in the environment. Environments are discussed in detail in the next section.

- A definition is handled as a special case. User-defined procedures are also discussed in the next section.

- A quoted expression evaluates to the text of the quotation, which is a string without the preceding quote. Sentences (represented as Python lists) are also considered to be quoted; they evaluate to themselves.

- A call expression looks up the operator name in the current environment and applies the procedure that is bound to that name.

A simplified implementation of logo_apply appears below. Some error checking has been removed in order to focus our discussion. A more robust implementation appears in the companion project.

>>> def logo_eval(line, env):

"""Evaluate the first expression in a line."""

token = line.pop()

if isprimitive(token):

return token

elif isvariable(token):

return env.lookup_variable(variable_name(token))

elif isdefinition(token):

return eval_definition(line, env)

elif isquoted(token):

return text_of_quotation(token)

else:

procedure = env.procedures.get(token, None)

return apply_procedure(procedure, line, env)

The final case above invokes a second process, procedure application, that is expressed by a function apply_procedure. To apply a procedure named by an operator token, that operator is looked up in the current environment. In the definition above, env is an instance of the Environment class described in the next section. The attribute env.procedures is a dictionary that stores the mapping between operator names and procedures. In Logo, an environment has a single such mapping; there are no locally defined procedures. Moreover, Logo maintains separate mappings, called separate namespaces, for the the names of procedures and the names of variables. A procedure and an unrelated variable can have the same name in Logo. However, reusing names in this way is not recommended.

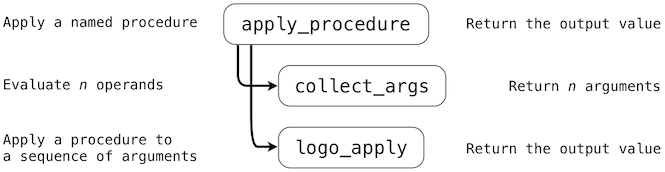

Procedure application. Procedure application begins by calling the apply_procedure function, which is passed the procedure looked up by logo_apply, along with the remainder of the current line of code and the current environment. The procedure application process in Logo is considerably more general than the calc_apply function in Calculator. In particular, apply_procedure must inspect the procedure it is meant to apply in order to determine its argument count n, before evaluating n operand expressions. It is here that we see why the Logo parser was unable to build an expression tree by syntactic analysis alone; the structure of the tree is determined by the procedure.

The apply_procedure function calls a function collect_args that must repeatedly call logo_eval to evaluate the next n expressions on the line. Then, having computed the arguments to the procedure, apply_procedure calls logo_apply, the function that actually applies procedures to arguments. The call graph below illustrates the process.

The final function logo_apply applies two kinds of arguments: primitive procedures and user-defined procedures, both of which are instances of the Procedure class. A Procedure is a Python object that has instance attributes for the name, argument count, body, and formal parameters of a procedure. The type of the body attribute varies. A primitive procedure is implemented in Python, and so its body is a Python function. A user-defined (non-primitive) procedure is defined in Logo, and so its body is a list of lines of Logo code. A Procedure also has two boolean-valued attributes, one to indicated whether it is primitive and another to indicate whether it needs access to the current environment.

>>> class Procedure():

def __init__(self, name, arg_count, body, isprimitive=False,

needs_env=False, formal_params=None):

self.name = name

self.arg_count = arg_count

self.body = body

self.isprimitive = isprimitive

self.needs_env = needs_env

self.formal_params = formal_params

A primitive procedure is applied by calling its body on the argument list and returning its return value as the output of the procedure.

>>> def logo_apply(proc, args):

"""Apply a Logo procedure to a list of arguments."""

if proc.isprimitive:

return proc.body(*args)

else:

"""Apply a user-defined procedure"""

The body of a user-defined procedure is a list of lines, each of which is a Logo sentence. To apply the procedure to a list of arguments, we evaluate the lines of the body in a new environment. To construct this environment, a new frame is added to the environment in which the formal parameters of the procedure are bound to the arguments. The important structural aspect of this process is that evaluating a line of the body of a user-defined procedure requires a recursive call to eval_line.

Eval/apply recursion. The functions that implement the evaluation process, eval_line and logo_eval, and the functions that implement the function application process, apply_procedure, collect_args, and logo_apply, are mutually recursive. Evaluation requires application whenever a call expression is found. Application uses evaluation to evaluate operand expressions into arguments, as well as to evaluate the body of user-defined procedures. The general structure of this mutually recursive process appears in interpreters quite generally: evaluation is defined in terms of application and application is defined in terms of evaluation.

This recursive cycle ends with language primitives. Evaluation has a base case that is evaluating a primitive expression, variable, quoted expression, or definition. Function application has a base case that is applying a primitive procedure. This mutually recursive structure, between an eval function that processes expression forms and an apply function that processes functions and their arguments, constitutes the essence of the evaluation process.

3.6.4 Environments

Now that we have described the structure of our Logo interpreter, we turn to implementing the Environment class so that it correctly supports assignment, procedure definition, and variable lookup with dynamic scope. An Environment instance represents the collective set of name bindings that are accessible at some point in the course of program execution. Bindings are organized into frames, and frames are implemented as Python dictionaries. Frames contain name bindings for variables, but not procedures; the bindings between operator names and Procedure instances are stored separately in Logo. In the project implementation, frames that contain variable name bindings are stored as a list of dictionaries in the _frames attribute of an Environment, while procedure name bindings are stored in the dictionary-valued procedures attribute.

Frames are not accessed directly, but instead through two Environment methods: lookup_variable and set_variable_value. The first implements a process identical to the look-up procedure that we introduced in the environment model of computation in Chapter 1. A name is matched against the bindings of the first (most recently added) frame of the current environment. If it is found, the value to which it is bound is returned. If it is not found, look-up proceeds to the frame that was extended by the current frame.

The set_variable_value method also searches for a binding that matches a variable name. If one is found, it is updated with a new value. If none is found, then a new binding is created in the global frame. The implementations of these methods are left as an exercise in the companion project.

The lookup_variable method is invoked from logo_eval when evaluating a variable name. The set_variable_value method is invoked by the logo_make function, which serves as the body of the primitive make procedure in Logo.

>>> def logo_make(symbol, val, env):

"""Apply the Logo make primitive, which binds a name to a value."""

env.set_variable_value(symbol, val)

With the addition of variables and the make primitive, our interpreter supports its first means of abstraction: binding names to values. In Logo, we can now replicate our first abstraction steps in Python from Chapter 1:

? make "radius 10

? print 2 * :radius

20

Assignment is only a limited form of abstraction. We have seen from the beginning of this course that user-defined functions are a critical tool in managing the complexity of even moderately sized programs. Two enhancements will enable user-defined procedures in Logo. First, we must describe the implementation of eval_definition, the Python function called from logo_eval when the current line is a definition. Second, we will complete our description of the process in logo_apply that applies a user-defined procedure to some arguments. Both of these changes leverage the Procedure class defined in the previous section.

A definition is evaluated by creating a new Procedure instance that represents the user-defined procedure. Consider the following Logo procedure definition:

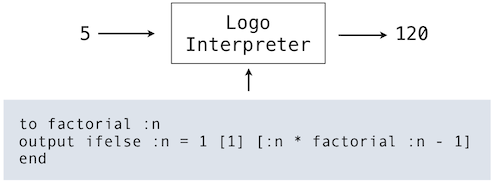

? to factorial :n

> output ifelse :n = 1 [1] [:n * factorial :n - 1]

> end

? print fact 5

120

The first line of the definition supplies the name factorial and formal parameter n of the procedure. The line that follows constitute the body of the procedure. This line is not evaluated immediately, but instead stored for future application. That is, the line is read and parsed by eval_definition, but not passed to eval_line. Lines of the body are read from the user until a line containing only end is encountered. In Logo, end is not a procedure to be evaluated, nor is it part of the procedure body; it is a syntactic marker of the end of a procedure definition.

The Procedure instance created from this procedure name, formal parameter list, and body, is registered in the procedures dictionary attribute of the environment. In Logo, unlike Python, once a procedure is bound to a name, no other definition can use that name again.

The logo_apply function applies a Procedure instance to some arguments, which are Logo values represented as strings (for words) and lists (for sentences). For a user-defined procedure, logo_apply creates a new frame, a dictionary object in which the the keys are the formal parameters of the procedure and the values are the arguments. In a dynamically scoped language such as Logo, this new frame always extends the current environment in which the procedure was called. Therefore, we append the newly created frame onto the current environment. Then, each line of the body is passed to eval_line in turn. Finally, we can remove the newly created frame from the environment after evaluating its body. Because Logo does not support higher-order or first-class procedures, we never need to track more than one environment at a time throughout the course of execution of a program.

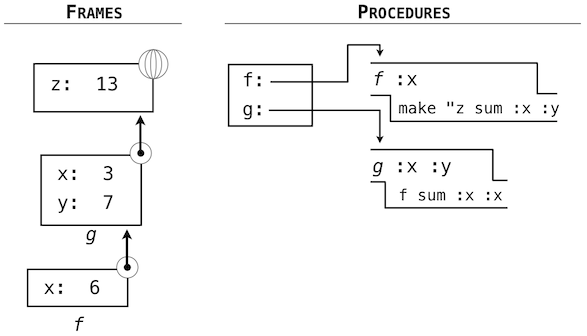

The following example illustrates the list of frames and dynamic scoping rules that result from applying these two user-defined Logo procedures:

? to f :x

> make "z sum :x :y

> end

? to g :x :y

> f sum :x :x

> end

? g 3 7

? print :z

13

The environment created from the evaluation of these expressions is divided between procedures and frames, which are maintained in separate name spaces. The order of frames is determined by the order of calls.

3.6.5 Data as Programs

In thinking about a program that evaluates Logo expressions, an analogy might be helpful. One operational view of the meaning of a program is that a program is a description of an abstract machine. For example, consider again this procedure to compute factorials:

? to factorial :n

> output ifelse :n = 1 [1] [:n * factorial :n - 1]

> end

We could express an equivalent program in Python as well, using a conditional expression.

>>> def factorial(n):

return 1 if n == 1 else n * factorial(n - 1)

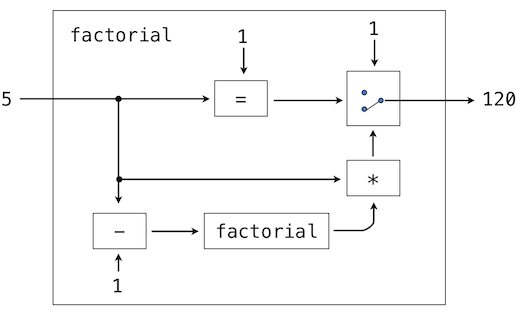

We may regard this program as the description of a machine containing parts that decrement, multiply, and test for equality, together with a two-position switch and another factorial machine. (The factorial machine is infinite because it contains another factorial machine within it.) The figure below is a flow diagram for the factorial machine, showing how the parts are wired together.

In a similar way, we can regard the Logo interpreter as a very special machine that takes as input a description of a machine. Given this input, the interpreter configures itself to emulate the machine described. For example, if we feed our evaluator the definition of factorial the evaluator will be able to compute factorials.

From this perspective, our Logo interpreter is seen to be a universal machine. It mimics other machines when these are described as Logo programs. It acts as a bridge between the data objects that are manipulated by our programming language and the programming language itself. Image that a user types a Logo expression into our running Logo interpreter. From the perspective of the user, an input expression such as sum 2 2 is an expression in the programming language, which the interpreter should evaluate. From the perspective of the Logo interpreter, however, the expression is simply a sentence of words that is to be manipulated according to a well-defined set of rules.

That the user's programs are the interpreter's data need not be a source of confusion. In fact, it is sometimes convenient to ignore this distinction, and to give the user the ability to explicitly evaluate a data object as an expression. In Logo, we use this facility whenever employing the run procedure. Similar functions exist in Python: the eval function will evaluate a Python expression and the exec function will execute a Python statement. Thus,

>>> eval('2+2')

4

and

>>> 2+2

4

both return the same result. Evaluating expressions that are constructed as a part of execution is a common and powerful feature in dynamic programming languages. In few languages is this practice as common as in Logo, but the ability to construct and evaluate expressions during the course of execution of a program can prove to be a valuable tool for any programmer.